Fire ants and electric fish

But back when Victor was in high school in Orlando and he wanted to be a biologist, he figured that was someone who does field work studying plants and animals. So when he enrolled as an undergraduate at Florida State, he joined a lab that studied fire ants. That’s where the neuroscience bug started to bite (thankfully not literally). What interested him in particular was the ants’ behavior.

His mentor there, Professor Walter Tschinkel, suggested that the best way to explore his interest in science was to read papers and see what interested him most. What jumped out was research by Wash U Associate Professor Bruce Carlson, who studied fish that navigate murky waters by generating weak electrical pulses like bats or dolphins use sonar.

Victor reached out to Carlson about joining his lab when he went to graduate school. In the interim, Carlson introduced him to research colleague José Alves-Gomes who was doing fieldwork with the fish in Brazil – though in the Amazon rainforest, which is a world away from arid Recife. While Victor was studying the fish and learning about the neuroscience of how they sense with electricity, he began applying for research jobs to bridge a few years between college and graduate school.

He landed a job in a lab at Columbia University. There he learned how neural stem cells become neurons and how the cellular environment helps to determine that. He also met his wife, Alexis Hill, who is now an assistant professor of neuroscience at College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Mass.

“A lot of these kids had just arrived,” he said. “That really sparked me and made me understand my responsibility in using this awesome privilege that I have to give more opportunities like this to kids who wouldn’t otherwise have them.”

After two years in New York, Victor went to WashU for grad school, and Hill did her postdoc there. It was at the elite Midwestern school that Victor first realized he had a Latino identity. He had never really felt like he was a minority in Florida or New York where there were so many other Latinos. In Brazil, in fact, he was considered “white.”

“It was the first time where I felt that my race mattered,” he said.

His response was to embrace the power that he had to encourage Latino children to consider science. He and fellow minority graduate students identified a local population of mostly Mexican children.

“A lot of these kids had just arrived,” he said. “That really sparked me and made me understand my responsibility in using this awesome privilege that I have to give more opportunities like this to kids who wouldn’t otherwise have them.”

To MIT

As a graduate student, Victor rotated through labs including Carlson’s, but he realized that he had become more interested in neural cell development. He joined the lab of Andrew Yoo, who uses brain-enriched microRNAs to reprogram human skin cells into neurons. In his thesis work Victor developed a way to coax skin cells into becoming the specific kind of neuron that degenerates in Huntington’s disease, providing a testbed for research derived from cells from patients with the condition. He led two papers from the work, in Neuron and Nature Neuroscience.

During that time, Tsai came to WashU to speak and Victor learned that her lab did a substantial amount of work with cellular reprogramming, too. Not long after, he contacted her and invited her to visit his poster at the 2016 Society for Neuroscience Annual meeting in San Diego. She did, and from there they struck up a frequent correspondence. For nearly two years, she continued to encourage him to pursue his work, to apply for fellowships such as the Hanna Gray, and to come to MIT.

“She’s been very invested in my progress and my future,” he said. “It’s just really awesome.”

He interviewed to join Tsai’s lab in January 2017.

“I really enjoyed everyone I met,” he said. “I was so blown away by all the postdocs here. After every meeting I was like, ‘Wow, I want to become best friends with this person,’ or ‘Wow, I want to hang out with this person’.”

The feeling is mutual, Tsai said.

“He fits right in and meshes well with everyone in the lab,” she said. “He is kind and friendly and always willing to help.”

Now, with the support of the lab and the fellowship, Victor is interested in two projects.

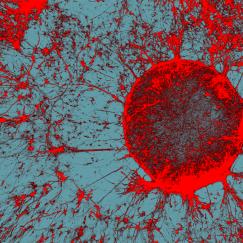

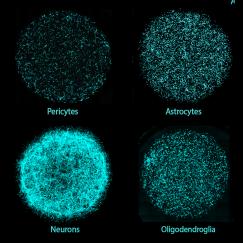

In one he plans to turn human induced pluripotent stem cells (IPSCs) into microglia, an immune cell of the nervous system increasingly implicated in Alzheimer’s disease, and implant them in the brains of mice where the original microglia have been removed. With this chimera model Victor can test how microglia with different genetic variations act in a mammalian brain to see how those variations might contribute to disease pathology. In the other, he is interested in studying how inhibitory interneurons change in the aging brain. The neurons are of particular interest because they are the source of a crucial brain rhythm that is notably reduced in Alzheimer’s disease. Understanding more about how they function and falter could help explain that important change.

Then, about four years from now, Victor will start his own lab. With continued support from the fellowship, he’ll be able to embark on a career of not only reaching his own potential but also helping the next generation have the privilege of pursuing their interests, too.