In recent decades the life expectancy of people with Down syndrome has surged past 60 years, so the focus of research at the Alana Down Syndrome Center at MIT has been to make sure people can enjoy the best health during that increasing timeframe.

“A person with Down syndrome can live a long and happy life,” said Rosalind Mott Firenze, scientific director of the center founded at MIT in 2019 with a gift from the Alana Foundation. “So the question is now how do we improve health and maximize ability through the years? It’s no longer about lifespan, but about healthspan.”

Firenze and three of the center’s Alana Fellows scientists spoke during a webinar, hosted on April 17th, where they described the center’s work toward that goal. An audience of 99 people signed up to hear the webinar titled “Building a Better Tomorrow for Down Syndrome Through Research and Technology,” with many viewers hailing from the Massachusetts Down Syndrome Congress, which co-sponsored the event.

The research they presented covered ways to potentially improve health from stages before birth to adulthood in areas such as brain function, heart development, and sleep quality.

Above: Scientist speakers Dong Shin Park, Rosalind Mott Firenze, Leah Borden and Md Rezaul Islam begin the webinar, "Building a Better Tommorrow for Down Syndrome through Research and Technology."

Boosting brain waves

One of the center’s most important areas of research involves testing whether boosting the power of a particular frequency of brain activity—“gamma” brain waves of 40Hz—can improve brain development and function. The lab of the center’s Director Li-Huei Tsai, Picower Professor in The Picower Institute for Learning and Memory and the Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences, uses light that flickers and sound that clicks 40 times a second to increase that rhythm in the brain. In early studies of people with Alzheimer’s disease, which is a major health risk for people with Down syndrome, the non-invasive approach has proved safe, and appears to improve memory while preventing brain cells from dying. The reason it works appears to be because it promotes a healthy response among many types of brain cells.

Working with mice that genetically model Down syndrome, Alana Fellow Dong Shin Park has been using the sensory stimulation technology to study whether the healthy cellular response can affect brain development in a fetus while a mother is pregnant. In ongoing research, he said, he’s finding that exposing pregnant mice to the light and sound appears to improve fetal brain development and brain function in the pups after they are born.

In his research, Postdoctoral Associate Md. Rezaul Islam worked with 40Hz sensory stimulation and Down syndrome model mice at a much later stage in life—when they are adult aged. Together with former Tsai Lab member Brennan Jackson, he found that when the mice were exposed to the light and sound, their memory improved. The underlying reason seemed to be an increase not only in new connections among their brain cells, but also an increase in the generation of new ones. The research, currently online as a preprint, is set to publish in a peer-reviewed journal very soon.

Firenze said the Tsai lab has also begun to test the sensory stimulation in human adults with Down syndrome. In that testing, which is led by Dr. Diane Chan, it is proving safe and well tolerated, so the lab is hoping to do a year-long study with volunteers to see if the stimulation can delay or prevent the onset of Alzheimer’s disease.

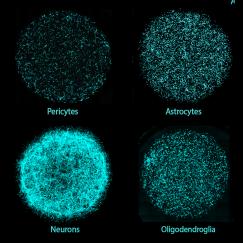

Studying cells

Many Alana Center researchers are studying other aspects of the biology of cells in Down syndrome to improve healthspan. Leah Borden, an Alana Fellow in the lab of Biology Professor Laurie Boyer, is studying differences in heart development. Using advanced cultures of human heart tissues grown from trisomy 21 donors, she is finding that tissue tends to be stiffer than in cultures made from people without the third chromosome copy. The stiffness, she hypothesizes, might affect cellular function and migration during development, contributing to some of the heart defects that are common in the Down syndrome population.

Firenze pointed to several other advanced cell biology studies going on in the center. Researchers in the lab of Computer Science Professor Manolis Kellis, for instance, have used machine learning and single cell RNA sequencing to map the gene expression of more than 130,000 cells in the brains of people with or without Down syndrome to understand differences in their biology.

Researchers the lab of Y. Eva Tan Professor Edward Boyden, meanwhile, are using advanced tissue imaging techniques to look into the anatomy of cells in mice, Firenze said. They are finding differences in the structures of key organelles called mitochondria that provide cells with energy.

And in 2022, Firenze recalled, Tsai’s lab published a study showing that brain cells in Down syndrome mice exhibited a genome-wide disruption in how genes are expressed, leading them to take on a more senescent, or aged-like, state.

Striving for better sleep

One other theme of the Alana Center’s research that Firenze highlighted focuses on ways to understand and improve sleep for people with Down syndrome. In mouse studies in Tsai’s lab, they’ve begun to measure sleep differences between model and neurotypical mice to understand more about the nature of sleep disruptions.

“Sleep is different and we need to address this because it’s a key factor in your health,” Firenze said.

Firenze also highlighted how the Alana Center has collaborated with MIT’s Desphande Center for Technological Innovation to help advance a new device for treating sleep apnea in people with Down syndrome. Led by Mechanical Engineering Associate Professor Ellen Roche, the ZzAlign device improves on current technology by creating a custom-fit oral prosthesis accompanied by just a small tube to provide the needed air pressure to stabilize mouth muscles and prevent obstruction of the airway.

Through many examples of research projects aimed at improving brain and heart health and enhancing sleep, the webinar presented how MIT’s Alana Down Syndrome Center is working to advance the healthspan of people with Down syndrome.