Estimates vary, but if you took away all the cells in the human brain that aren’t neurons, you’d be left with half the brain. So what are all those neural neighbors doing there?

The vasculature circulates blood, of course, but for the rest of the cells the earliest guess in the 1800s was that they just held neurons together, earning them the collective name “glia,” the Greek word for glue. Neuroscientists have come a long way from that starting point. Today some of the most exciting discoveries in The Picower Institute and the broader field are being made in various glial cells and the cells of the brain’s vasculature, whose complexity and consequence are both gaining recognition. These studies are making two things increasingly clear: non-neuronal cells are intimately involved in enabling sophisticated functions including learning and memory, and they are critical co-conspirators in disease.

New technologies have enabled a recent acceleration of new findings, said Newton Professor Mriganka Sur. His leadership in the field earned him the invitation to be a panelist in a discussion of glia and brain function at last year’s Society for Neuroscience Annual Meeting. In a companion paper of the event in the Journal of Neuroscience, the panelists wrote, “A broader role of glia in the central nervous system has begun to emerge, pointing out these cells’ regulatory role in complex, higher-order brain functions and behaviors.”

As Sur has published discoveries about how glial cells called astrocytes contribute to learning and memory, John and Dorothy Wilson Associate Professor Myriam Heiman has revealed mechanisms of how blood vessels become compromised in the neurodegenerative disorders Huntington’s disease, frontotemporal dementia, and ALS. And Picower Professor Li-Huei Tsai has published numerous studies over the last decade identifying ways in which the catastrophe of Alzheimer’s disease manifests not only in the vasculature, but also the three major glial cell types: microglia, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes.

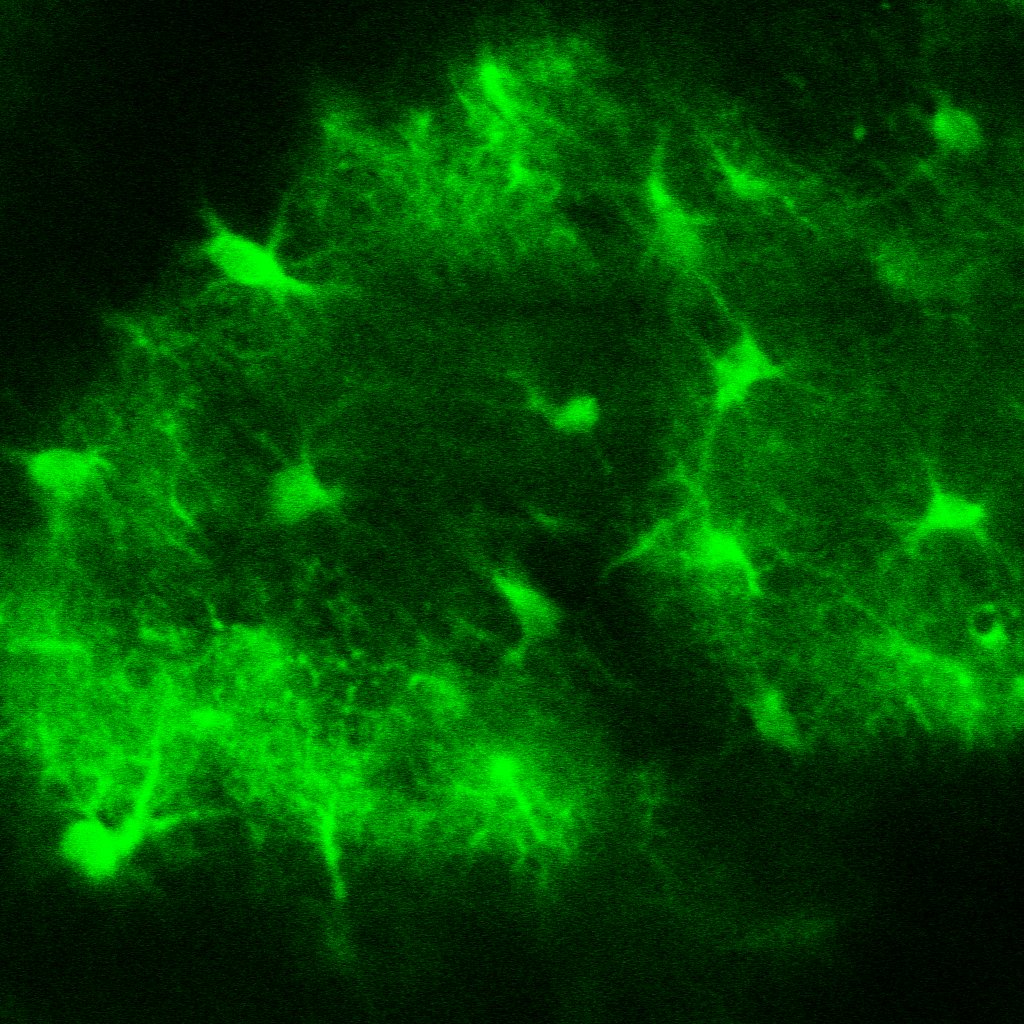

Above: Microglia, stained red, fill the field of view in this image created as part of research published by the Tsai lab in 2023. Image courtesy Mat Victor.

While it might seem like bleak news that diseases known for killing neurons also involve glia and the vasculature, Heiman says that actually presents an opportunity. For instance, many diseases show similar dysfunction in the cerebrovasculature that may be easier to target than problems lurking in neurons.

“Across all of these diseases, Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, ALS, and Huntington’s, vascular dysfunction has been noted, so could there be a therapeutic that would be easily administered in the blood because it targets blood vessels?” Heiman said. “Such a therapeutic could be effective across disorders and thus very appealing.”

Meet the neighbors

To better understand how glial cells and the vasculature both enable healthy brain function and participate in disease dysfunction, let’s meet the major types.

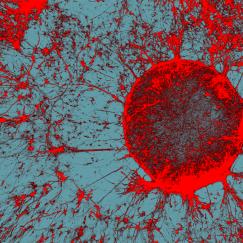

- Astrocytes: Sur cites two factoids that illustrate how crucial astrocytes are—They may be more numerous than neurons in the human brain and each one may directly contact as many as 100,000 “synapses”—the circuit connections neurons forge with each other. Astrocytes can manage levels of the neurotransmitter chemicals that facilitate communication across synapses. They also grasp blood vessels to help regulate blood flow and what gets exchanged with the blood, and they can provide neurons with chemical energy.

- Microglia: The brain’s immune cells sense damage and disease and manage inflammation responses. They also gobble up waste and debris. During development, this job includes destroying synapses that are no longer necessary. Such “synaptic pruning” is an essential function for helping brain circuits mature.

- Oligodendrocytes: Neurons have that long extension (called an “axon”) that reaches out to forge synapses with other cells. Oligodendrocytes specialize in wrapping axons in a fatty insulation called myelin that enables faster transmission of electrical signals. This vital process for making neural circuits work well is notably compromised in diseases such as Alzheimer’s.

- Vascular cells: In 2022, Heiman co-led one of the first cellular “atlases” of the brain’s vasculature. Her team cataloged 11 different subtypes of cells that make vessels function not as passive conduits of blood flow, but as dynamic and responsive tissues that stringently filter what molecular materials can move through the “blood-brain barrier.”

Glia in learning and memory

In 2023 Sur’s lab studied the role of astrocytes in learning movement skills. They trained mice to push a lever after hearing a tone. Then in some mice the scientists disrupted their astrocytes’ ability to soak up the neurotransmitter glutamate. This intervention caused the mice’s motions to become erratic. In other mice they hyperactivated the astrocytes’ ability to signal neurons with calcium. This not only undermined the smoothness of the mice’s motions, but also impeded their ability to learn the task and their reaction time after hearing the cue tone. Under the microscope, in both cases, the researchers could see why behavior got worse. For lack of proper astrocyte function, the coordination among groups of neurons responsible for controlling the movements became compromised.

A “preprint” (i.e. not yet peer reviewed) study from the lab posted late last year provided another example of how astrocyte regulation of neurotransmitters affects learning. Sur lab members used CRISPR gene editing to disrupt how astrocytes maintain the supply of the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA in neurons of the visual cortex. Doing so impaired the ability of the mice to properly represent (in patterns of neural activity) what they were seeing.

In another study in 2022, Sur’s lab investigated how surprise helps the brain learn. For instance, if a move you make on the chessboard has disastrous consequences, you really remember that. The surprise signal is carried by the neuromodulatory chemical norepinephrine. In the study, mice were trained in a motor task with an uncertain cue. The mice were therefore sometimes surprised to learn, via an irritating puff of air, that they responded wrong. But somehow after neurons in the prefrontal cortex (responsible for reasoning about what to do) received a transient norepinephrine signal, the mice adjusted their behavior to reflect the correction on the next go-round.

“But there is a conundrum, which is that the responses that we recorded after a false alarm, they kind of die out,” Sur said. “There is not enough activity that we could see overtly persisting several seconds later until the next trial. Yet in the next trial, when the stimulus comes on, the neuronal responses are reorganized.”

That’s where astrocytes come in. In a new preprint, Sur’s lab provides evidence that the noradrenaline acts not on neurons but on astrocytes. It triggers a sustained increase in their calcium levels. That promotes them to release chemicals that are usually associated with energy metabolism to signal neurons to alter their activity. “So that’s our story, that the norepinephrine system actually acts via astrocytes, which then influence neurons,” Sur said. “Therefore, astrocytes are not only not handmaidens, they are actually crucial for this very important behavior of reinforcement learning.”

What about other cell types and mechanisms of memory? For years, Tsai has shown that in the rush to encode a memory, neurons will snap open both strands of their DNA to enable rapid expression of the genes responsible. In 2021, though, her lab found a surprising result when they dug deeper into how mice remember stressful events (like getting a little shock on the foot). When they looked at all cells –not just neurons—they found that many glia also employed double-strand breaks for rapid response, particularly to express genes associated with glucocorticoid hormones, which signal stress. This suggests that the glia played a key role in incorporating the mouse’s sense of stress in encoding the memory.

As noted above, microglia help refine neural circuits. Oligodendrocytes do, too. In a study in 2020, William and Linda R. Young Professor Elly Nedivi and colleagues at Harvard showed that one of the ways that visual cortex neurons change to incorporate new visual experiences is by changing their myelin. The study showed how oligodendrocytes contribute to that dynamic.

Roles in disease

The inevitable corollary of glia having important roles in healthy brain function is that when things go wrong with them, brain function suffers, too. Tsai’s lab has illustrated this via an investigation of why the APOE4 variation of the APOE gene constitutes the biggest genetic risk factor for Alzheimer’s.

In five papers spanning 2018-2022, her lab engineered cultures of neurons, astrocytes, microglia, oligodendrocytes and the vasculature in which cells bearing APOE3 could be compared with cells whose only difference was harboring APOE4. In each case the researchers showed how the variation undermined their function. APOE4 microglia, for instance, left excess fat molecules, or lipids, in the environment around neurons. The lipids bound to potassium channels on the neurons, degrading their electrical activity. Astrocytes with APOE4 became overwhelmed by a buildup of cholesterol and triglycerides that affected many crucial functions. Oligodendrocytes with APOE4 failed to properly transport cholesterol to myelinate axons. And in a complex multicellular culture the lab developed of the vasculature and the blood brain barrier (BBB), they found that when pericyte cells have APOE4, they churn out too much APOE protein, which causes amyloid to clump together in blood vessels undermining BBB performance.

Tsai’s lab has identified other problems with microglia and oligodendrocytes amid Alzheimer’s disease. A landmark paper in 2015 analyzed gene expression patterns amid the disease, finding that many genes associated with Alzheimer’s were most active in microglia and that they promoted an inflammatory response. A follow up study in 2023 showed that microglia take on as many as 12 distinct states in Alzheimer’s. As the disease progresses, more microglia assume inflammatory states and fewer remain in states that promote normal brain function.

The later study employed the emerging technology of single cell RNA sequencing (scRNAseq) to examine differences in gene expression, cell by cell, in Alzheimer’s vs. comparable non-Alzheimer’s brain samples. In 2019, when Tsai and colleagues used the method to map gene expression in the Alzheimer’s brain, they produced new insights into why myelination suffers during the disease, especially among women. In some good news, another scRNAseq study in 2024 showed that when astrocytes express genes associated with antioxidant activity and metabolism of the nutrient choline, that helps protect the brain from Alzheimer’s.

When Heiman and colleagues used scRNAseq to create their atlas of cell types in the cerebrovasculature in 2022, it wasn’t just for cellular cartography. Heiman studies neurodegenerative diseases including Huntington’s disease and for years she and her lab had been curious about why patients exhibit cerebrovascular abnormalities long before they show other disease symptoms. So Heiman’s team not only studied healthy brains, but also ones with Huntington’s. In doing so, her team showed a deficit of expression in key BBB proteins and abnormal innate immune activation in the endothelial cells that line blood vessels.

In a separate study last year, Heiman’s collaboration looked at brains with ALS and a kind of frontotemporal dementia. There, too, they found direct evidence that in these neurodegenerative disorders, expression of proteins needed to maintain the BBB is impaired.

And notably, in a recent preprint, Sur’s lab combined many of the techniques described above to show that the BBB suffers in the neurodevelopmental disorder Rett syndrome because of a specific molecular defect in vascular endothelial cells.

Non-neuronal therapies

The identification of specific genetic or molecular problems in non-neuronal cells gives Heiman new hope for developing therapies. It means that scientists are not confined to intervening in neurons.

“Improving the health of the cerebrovasculature has promise for maintaining brain healthspan both in normal aging and in disease,” Heiman said. “Are there ways that, for example, one could target gene therapy to the cerebrovasculature of the brain to promote its health? Could that help delay onset of disease symptoms across neurodegenerative diseases? Those are questions we and others in the field are actively pursuing right now.”

In each of her APOE4 studies, Tsai has demonstrated specific compounds or drugs that can rescue the deficiencies she’s detected in glial or vascular cells. She’s testing the finding that choline, a common nutrient, aids APOE4 astrocytes in a clinical trial. Moreover, Tsai has developed several experimental drugs in her lab that, in different ways, target molecular mechanisms of microglial inflammation. For instance, last year she worked with MIT engineer Bob Langer to develop a lipid nanoparticle that delivers an RNA to microglia that suppresses the effects of an inflammation promoting protein she first identified in her 2015 study.

Also last year Tsai discovered that astrocytes and the vasculature play a key role in her research showing that stimulating the 40Hz gamma frequency rhythm in the brain can promote clearance of some of the amyloid protein that plagues Alzheimer’s brains. The clearance mechanism is the brain’s recently discovered “glymphatic” system, which is essentially a plumbing system of cerebrospinal fluid that runs alongside brain blood vessels. Tsai’s lab found that 40Hz activity induced by light and sound at that frequency stimulates certain neurons to release a peptide. The peptide makes the blood vessels pulsate, increasing the flow of fluid in the glymphatic system. It also causes astrocytes to open up more channels to let those fluids flow across the brain tissue, washing away amyloid.

Meanwhile, Sur and Heiman, in collaboration with Picower Institute Associate Professor Gloria Choi, have begun a project in which they are asking whether manipulating glial cells and the vasculature could help deliver a molecule with potential to help treat autism.

No one disputes the centrality of neurons in neuroscience, but studies of glia and cerebrovascular cells show that being the center of the neighborhood depends a great deal on the support of the neighbors