Femtoseconds and nanojoules

The theory behind multi-photon microscopy dates back to the 1931 doctoral dissertation of Maria Goeppert-Mayer, whose work showed that a simultaneous combination of lower-energy photons could excite an atom or molecule to a higher energy state just like a single higher energetic photon could. In 1990 Cornell University scientists applied that insight to biological imaging in the two-photon microscope and again in 2013 with a three-photon scope. These allowed neuroscientists to see deeper into the brain because lower energy, higher wavelength photons are less susceptible than higher-energy, shorter-wavelength photons to being scattered by cellular molecules like lipids.

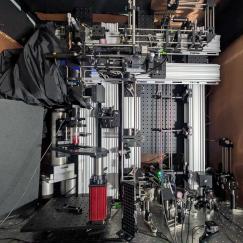

Sur and So’s labs at MIT have joined in pushing the frontiers of multiphoton microscopy. In the new study they show they’ve now taken it far enough to study live neural activity. To do that, the team sought to refine many different parameters of both the laser light and the scope optics, based on meticulous measurements of properties of the brain tissue they were imaging. For instance, they not only measured the energy at which cells started to show overt damage (about 10 nanojoules), but also measured the power at which cells would start to behave differently, thereby producing data influenced by the measurement (2 to 5 nanojoules). With precision and purpose to deliver lower energy levels, the scientists optimized the scope to emit incredibly short pulses of light lasting for a “pulse width” of only 40 femtoseconds, or quadrillionths of a second, and painstakingly arranged the optics to maximize the collection of the light that molecules, excited by the incoming laser energy, would emit back.

Unprecedented neuroscience

After carefully validating that the optimized three-photon scope’s measurements agreed with those of two-photon scopes (in shallower layers of the cortex) and electrophysiology (which can go deeper, but blindly), the team set out to do some unprecedented neuroscience – direct visual observation of neural activity in all cortical layers of awake, behaving animals.

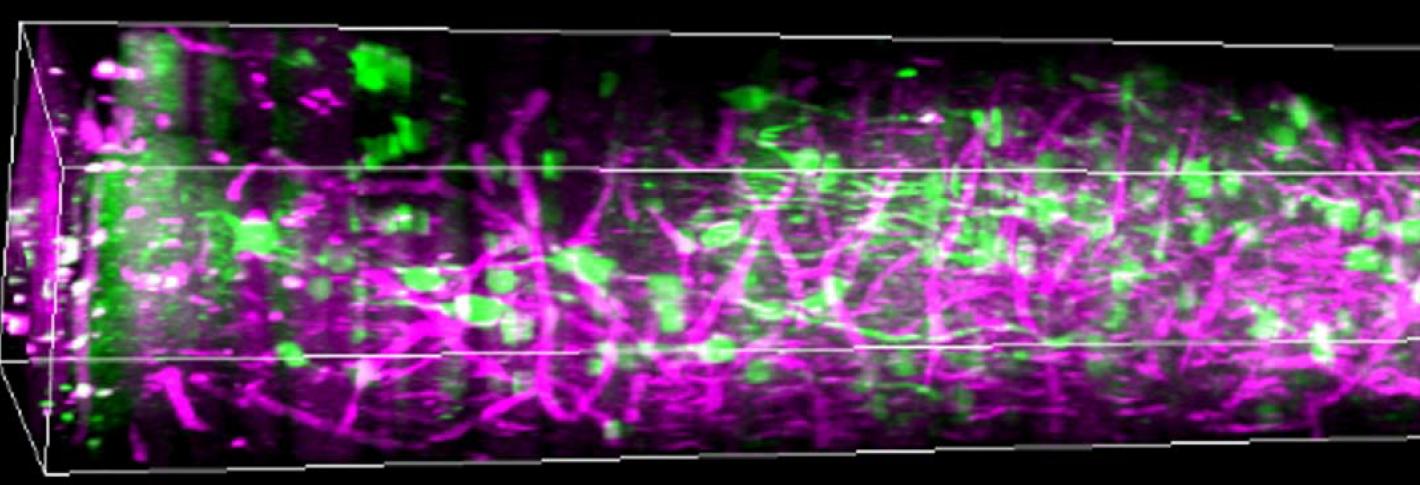

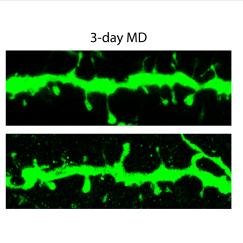

In the lab they showed mice some grating patterns in 12 different rotated orientations and two directions of motion across a screen. With their optimized three-photon scope, they watched neurons in each layer of the cortex – going more than a millimeter deep – to see how the cells reacted to this standard visual input. They could see the activity of the cells because they had engineered them to glow upon elevated calcium activity, using a label called GCaMP6s. They could see other tissues like blood vessels and white matter via a phenomenon called “third harmonic generation.”

With the capability to see the deepest layers they observed that layer 5 neurons are “broadly” tuned for orientation, meaning they respond to a wide variety of orientations, rather than just one or 2 specific ones. Layer 5 neurons also had more spontaneous activity than cells in other layers and more connections to deeper parts of the brain. Meanwhile, layer 6 neurons had somewhat sharper orientation tuning than neurons in other layers, meaning they are more specific in their response to distinct orientations.

Subplate surprise

Their most surprising finding was that the subplate, a thin layer of mostly neural “white-matter” fibers, was home to a population of neurons with patterns of activity that were weakly and broadly tuned to the visual input. The finding was revelatory, the researchers said, in that many neuroscientists believed that subplate neurons were mostly only active during development. The layer is also too thin, Yildirim said, to be measured with electrophysiology.

“So far, subplate neurons in the mature brain have not been studied at all due to the technical challenges of imaging these cells in vivo,” the researchers wrote.

Sugihara recalled the first time Yildirim showed him that subplate neurons were active in the mature mice. “What are they doing there?” he recalled asking in surprise.

Now they are continuing to use their new scope to answer that question.

The National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation, a Picower Institute Engineering Collaboration Grant and the Massachusetts Life Sciences Initiative supported the research.