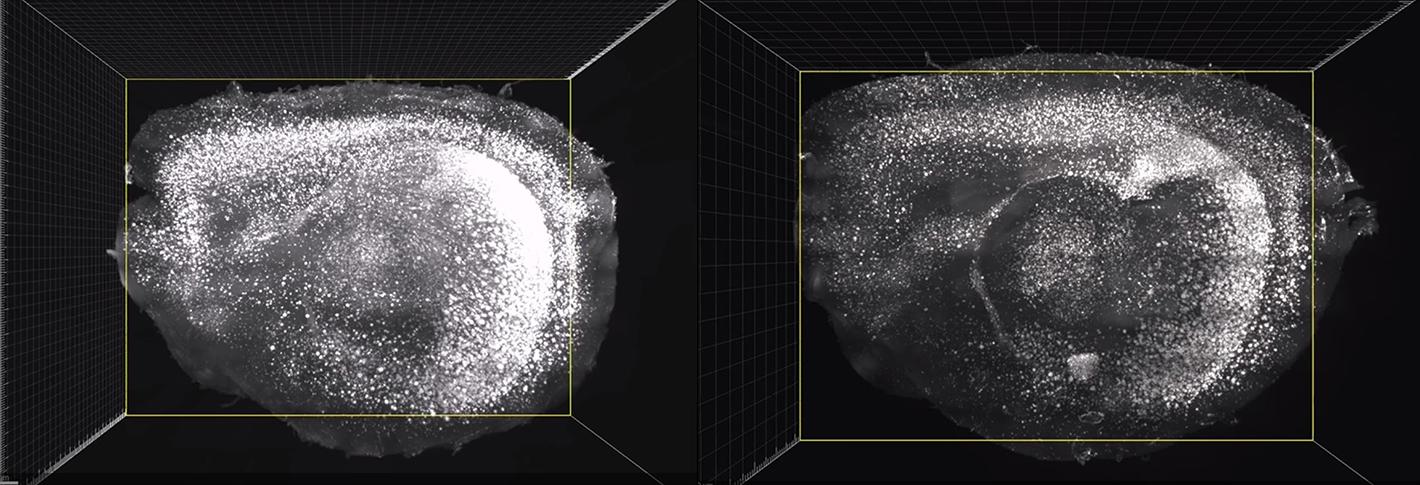

This noninvasive treatment, which works by inducing brain waves known as gamma oscillations, also greatly reduced the number of amyloid plaques found in the brains of these mice. Plaques were cleared in large swaths of the brain, including areas critical for cognitive functions such as learning and memory.

“When we combine visual and auditory stimulation for a week, we see the engagement of the prefrontal cortex and a very dramatic reduction of amyloid,” says Li-Huei Tsai, director of MIT’s Picower Institute for Learning and Memory and the senior author of the study.

Further study will be needed, she says, to determine if this type of treatment will work in human patients. The researchers have already performed some preliminary safety tests of this type of stimulation in healthy human subjects.

MIT graduate student Anthony Martorell and Georgia Tech graduate student Abigail Paulson are the lead authors of the study, which appears in the March 14 issue of Cell.

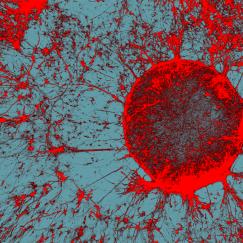

Above: In mouse brains stained for the presence of amyloid, much less is visible in the cortex of a mouse treated with sensory gamma stimulation (right) than in a mouse left untreated (left). SHIELD (Park, NBT, 2019), Stochastic Electrotransport (Kim, PNAS, 2015), and eFLASH (unpublished) technologies developed by the Kwanghun Chung Lab were used for the brain preservation, clearing, and labeling, respectively.

Memory improvement

The brain’s neurons generate electrical signals that synchronize to form brain waves in several different frequency ranges. Previous studies have suggested that Alzheimer’s patients have impairments of their gamma-frequency oscillations, which range from 25 to 80 hertz (cycles per second) and are believed to contribute to brain functions such as attention, perception, and memory.

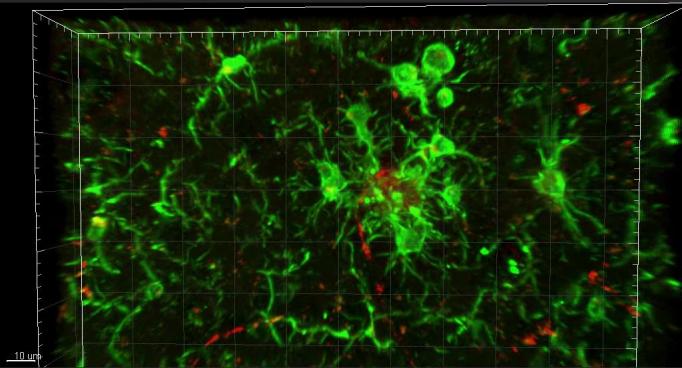

In 2016, Tsai and her colleagues first reported the beneficial effects of restoring gamma oscillations in the brains of mice that are genetically predisposed to develop Alzheimer’s symptoms. In that study, the researchers used light flickering at 40 hertz, delivered for one hour a day. They found that this treatment reduced levels of beta amyloid plaques and another Alzheimer’s-related pathogenic marker, phosphorylated tau protein. The treatment also stimulated the activity of debris-clearing immune cells known as microglia.

In that study, the improvements generated by flickering light were limited to the visual cortex. In their new study, the researchers set out to explore whether they could reach other brain regions, such as those needed for learning and memory, using sound stimuli. They found that exposure to one hour of 40-hertz tones per day, for seven days, dramatically reduced the amount of beta amyloid in the auditory cortex (which processes sound) as well as the hippocampus, a key memory site that is located near the auditory cortex.

“What we have demonstrated here is that we can use a totally different sensory modality to induce gamma oscillations in the brain. And secondly, this auditory-stimulation-induced gamma can reduce amyloid and Tau pathology in not just the sensory cortex but also in the hippocampus,” says Tsai, a founding member of MIT's Aging Brain Initiative.

The researchers also tested the effect of auditory stimulation on the mice’s cognitive abilities. They found that after one week of treatment, the mice performed much better when navigating a maze requiring them to remember key landmarks. They were also better able to recognize objects they had previously encountered.

They also found that auditory treatment induced changes in not only microglia, but also the blood vessels, possibly facilitating the clearance of amyloid.

Dramatic effect

The researchers then decided to try combining the visual and auditory stimulation, and to their surprise, they found that this dual treatment had an even greater effect than either one alone. Amyloid plaques were reduced throughout a much greater portion of the brain, including the prefrontal cortex, where higher cognitive functions take place. The microglia response was also much stronger.

“These microglia just pile on top of one another around the plaques,” Tsai says. “It’s very dramatic.”