Some of us labor to drive down our body fat percentage, so it might feel shocking to learn that the brain is estimated to be 60 percent fat. But don’t worry. The brain is fatty for good reason. Fats are essential for brain structure and function.

Various lipids compose the membranes of brain cells and form the vesicles that contain and transport the neurotransmitters that enable neuronal communication. To improve conduction of their electrical signals, most neurons insulate the long projections, or “axons,” that extend from their cell bodies with sheaths of a substance called myelin that is rich in cholesterol. And the power plants of energy-hungry neurons, mitochondria, fuel themselves with fatty acid molecules.

But with great responsibility comes great vulnerability. If brain cells mishandle lipid molecules, disease can result. A rapidly growing evidence base shows that’s exactly the case with Alzheimer’s disease. Many important papers providing that evidence have come from the lab of Picower Professor and Picower Institute director Li-Huei Tsai. A major arm of her lab’s research is dedicated to not only understanding the genetic, molecular and cellular basis for how lipid dysregulation drives Alzheimer’s disease pathology and symptoms, but also to turning that knowledge into potential therapies.

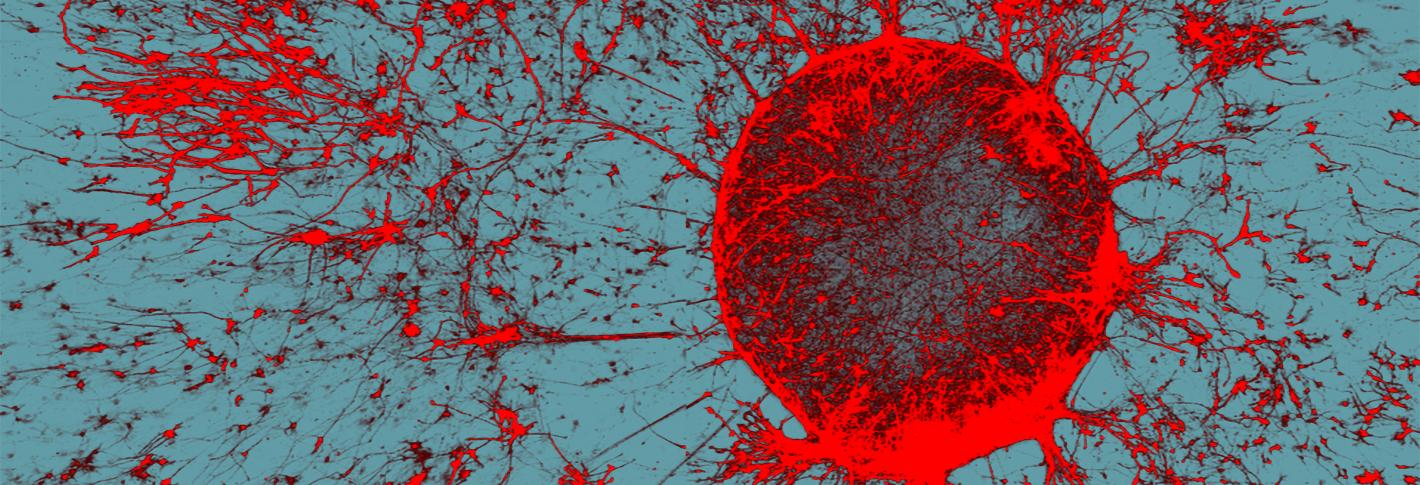

Alois Alzheimer documented abnormal fatty deposits in brain cells, but he also saw other pathology (amyloid plaques and tau tangles) that have attracted most of the attention since. And while researchers have known for about 30 years that the APOE4 variation of the cholesterol-transporting gene APOE is a huge risk factor, other genes have taken the limelight. But after looking at how APOE4 affects different brain cells in a study in 2018 in Neuron, Tsai’s lab has published a series of research articles that have put lipids at the center of Alzheimer's pathology in every major kind of brain cell.

Importantly, in each study her lab has not only identified specific problems with lipid regulation, but has also been able to identify a remedy that sets them right again.

“Once you normalize the lipid homeostasis in all these different cell types, you can reduce pathology,” said Tsai, who direct's MIT's Aging Brain Initiative. "That strongly suggests that lipid dysregulation contributes to the pathophysiology."

Fats and failure: Cell by cell

About a quarter of people on the planet have at least one copy of the APOE4 variant (vs. the benign APOE3 version). One copy increases the risk of developing Alzheimer’s by 3-fold, and having two copies increases it by more than 10-fold.

“We really are all in on APOE4,” Tsai said. “My lab is trying to do everything it can to understand APOE4.”

In that pioneering 2018 study, the lab took skin cells from donors and induced them to become stem cells. Then they turned those into three kinds of brain cells: neurons, microglia immune cells, and astrocytes. They edited some of the cells with CRISPR to make some of them carry APOE4, if they had APOE3, and vice versa. In each cell type they could see dramatic differences, including a big jump in cholesterol secretion by APOE4 astrocytes. Editing APOE4 cells to become APOE3 carriers corrected the problems, including the excess cholesterol in astrocytes.

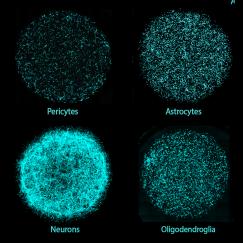

In several more studies over the next few years, the lab followed up on each cell type and also in oligodendrocytes, cells that produce myelin. Because each kind of cell has different jobs in the brain, Tsai said, the lab has found that lipid dysregulation undermines their function differently.

In 2021 in Science Translational Medicine, for example, the lab teamed up with that of the late Susan Lindquist at the Whitehead Institute to more deeply investigate astrocytes. Led by Grzegorz Sienski, Priyanka Narayan and Maeve Bonner, the team generated APOE3 and APOE4 versions of the cells and scrutinized their lipids. As before, the APOE4 astrocytes showed buildup of lipids, including triglycerides, which were unusually rich in chains of unsaturated fatty acids. The researchers also profiled lipids and gene expression in yeast cells engineered to have APOE4. The analyses showed that APOE4 yeast experienced a growth defect because of the same kinds of lipid disruptions evident in astrocytes. But the scientists also found a way to reverse it. Cells use a process called the Kennedy Pathway to help build cell membranes with lipids, and this process depends on levels of a common nutrient called choline (we get it from sources such as eggs, meats, beans and nuts). In choline-deficient media, APOE3 got by but APOE4 yeast couldn’t even survive. But with extra doses of choline, APOE4 yeast could grow normally. The scientists found that APOE4 cells needed more choline than APOE3 cells did. Moreover, when they gave the yeast cells or the astrocytes extra choline, their lipid imbalances were resolved, and the cells returned to healthier function.

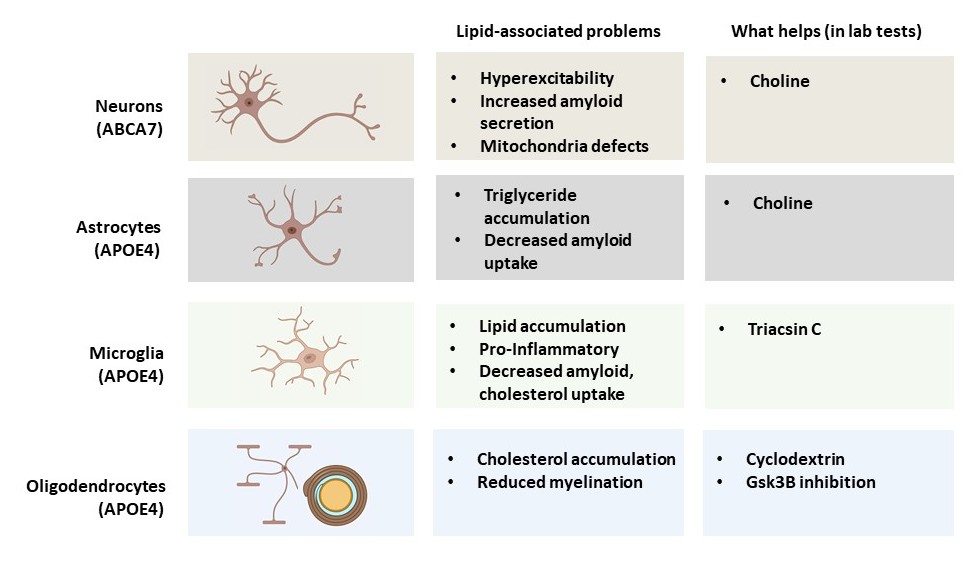

Top image: Neurons (red) in a cell culture from an experiment in 2022 where researchers showed that APOE4 microglia cells failed to support neuronal network communication. Credit: Matheus Victor, Assistant Professor at Mount Sinai School of Medicine.

The study also identified lipid dysregulation in microglia cells, but the Tsai lab’s focus on those cells came the next year in a study in Cell Stem Cell. There, Matheus Victor led the lab in discovering that an unwelcome buildup of lipids in APOE4 microglia not only made them more inflammatory, but also compromised their ability to clean up cholesterol from the space they shared with neighboring neurons. That excess extracellular cholesterol turned out to disrupt the neurons’ ability to regulate their electrical excitation, which is key to their ability to communicate in brain circuits. But much like they found that choline could rescue APOE4 astrocytes, the team found in their cell cultures that the lipid droplet reducing drug Triacsin C rescued APOE4 microglia function and the electrical activity of their neural neighbors.

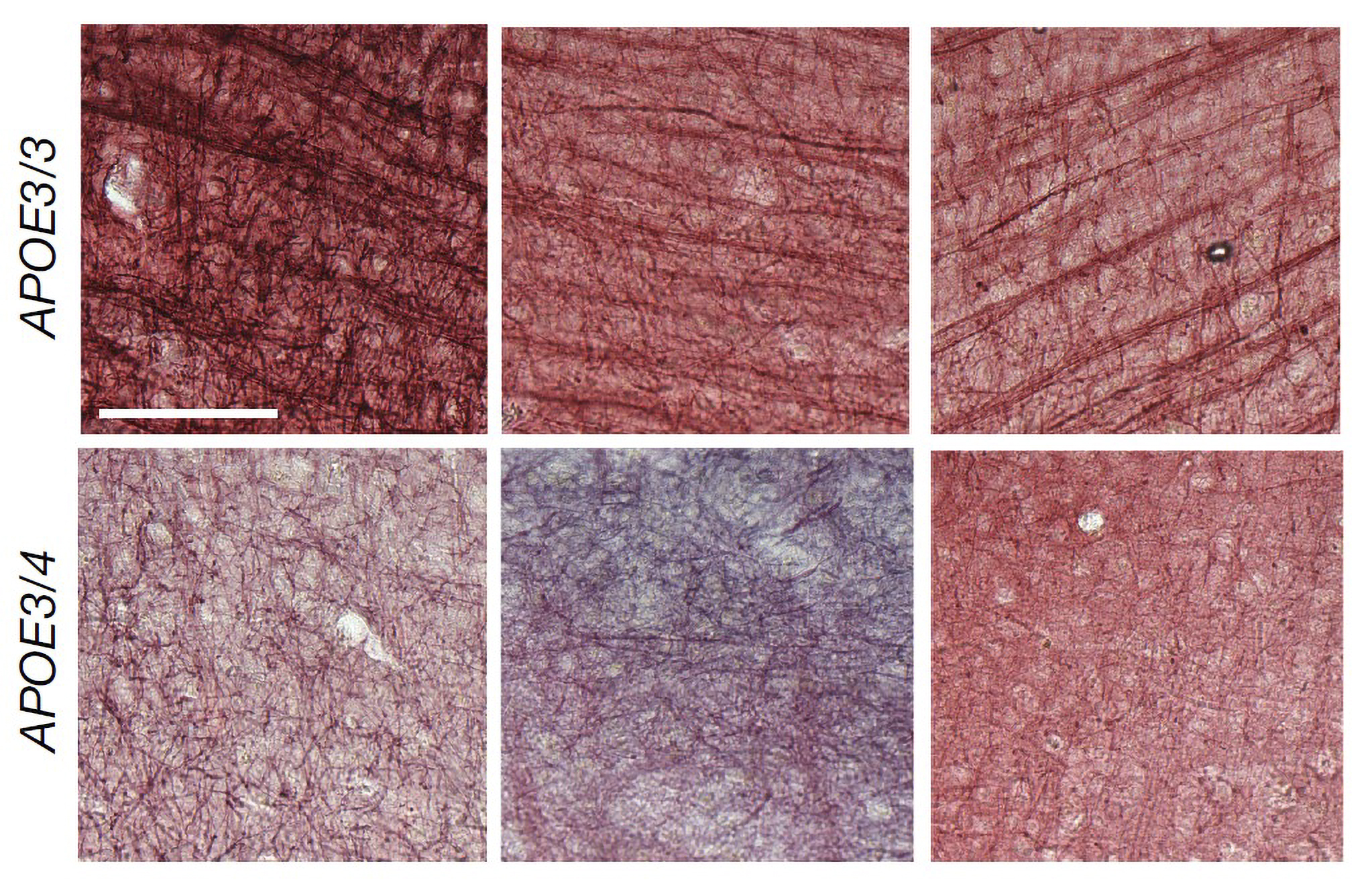

Later that year in Nature, Joel Blanchard, Leyla Akay and Djuna von Maydell led the lab in a study that looked at gene expression and lipidomic differences across different cell types in human brains with APOE4 vs. APOE3. They confirmed major differences in how cholesterol is handled in cells. APOE4 oligodendrocytes showed profound increases in cholesterol biosynthesis yet decreases in expression of myelination genes. They accumulated cholesterol within their cell bodies and failed to deploy it as myelin around neurons. Looking at post-mortem brain samples of APOE4-carrying people with Alzheimer’s the researchers saw significant deficits in myelination. But when they added the drug cyclodextrin, which facilitates cholesterol transport, APOE4 oligodendrocytes improved their myelination of neurons in co-culture. And in mice with APOE4, cyclodextrin improved myelination, learning and memory.

The studies have continued into this year. In a new preprint posted online, Akay dug deeper into how APOE4 oligodendrocytes over-accumulate lipids and discovered that hyperactivation of an enzyme called GSK3b is a linchpin. Inhibiting its activity, the team shows, reduces lipid droplets in the cells and improves myelination in mice.

And in September in Nature, von Maydell extended the lab’s studies of lipid-caused Alzheimer’s pathology and symptoms to the ABCA7 gene, which encodes a protein that transports lipids across cell membranes. Looking at gene expression changes in the brains of a dozen people with rare ABCA7 mutations, the team saw ominous effects on lipid metabolism, DNA damage, and mitochondrial function in neurons. Similar changes were also evident in neurons they cultured with ABCA7 mutations in the lab, which also exhibited hyperactivity and excessive amyloid secretion. A key aspect of the pathology turned out to be metabolism of phosphatidylcholine, which helps make membranes, including for mitochondria, potentially explaining their problems. As with astrocytes, supplements of choline helped correct the process in neurons. Amyloid and hyperactivity in cell cultures went down.

Going further with fats

Tsai notes that after years out of the clinical spotlight, lipids are now a focus at many pharmaceutical and startup companies.

And the Tsai lab is working on many new angles, too. In collaboration with MD Anderson Hospital in Houston and the University of Texas, Tsai has been testing choline in clinical studies with volunteers who have APOE4. The first round established useful biomarkers to set the table for a larger study that, if funded, will test for benefits.

Her lab is also using CRISPR to screen for genes or pathways that can be perturbed to help reverse the effects of APOE4 in different cell types. Von Maydell is leading an effort to employ artificial intelligence to better cluster Alzheimer’s patients in hopes of identifying subgroups that would be especially responsive to treatments. And former postdoc Rebecca Pinals, who just started her own lab at Stanford, is looking at molecular means of intervening in how lipids are trafficked in Alzheimer’s brains.

Given how closely many of us watch our fat intake (and accumulation), we might wonder whether lifestyle and diet changes could help, too. Tsai says, indeed, exercise and a healthy diet are considered protective, but the exact mechanisms aren’t yet clear. Another MIT project could help. Researchers in the Mechanical Engineering Department and in Tsai’s lab have teamed up to develop an AI tool that will combine a huge international study of preventative lifestyle factors with gene expression and other biological “-omics” data for cross-cutting analyses. In October, their plan became one of 10 semifinalists out of 200 entries in a $1 million contest funded by Bill Gates.

Around our waists, we often see fat as something to fight. In our heads, however, the game is a little more complex: Fats are everywhere, but in each cell type they need to be in the right balance and in the right forms and places. Figuring out how to ensure that could produce major advances against Alzheimer’s disease.