It’s one thing to make a brain completely transparent, but it’s another thing to do that and make it expandable so that everything inside can be seen bigger, too. That’s what MAP, or Magnified Analysis of Proteome, does. It makes tissues enlargeable so that small details can be seen even more easily.

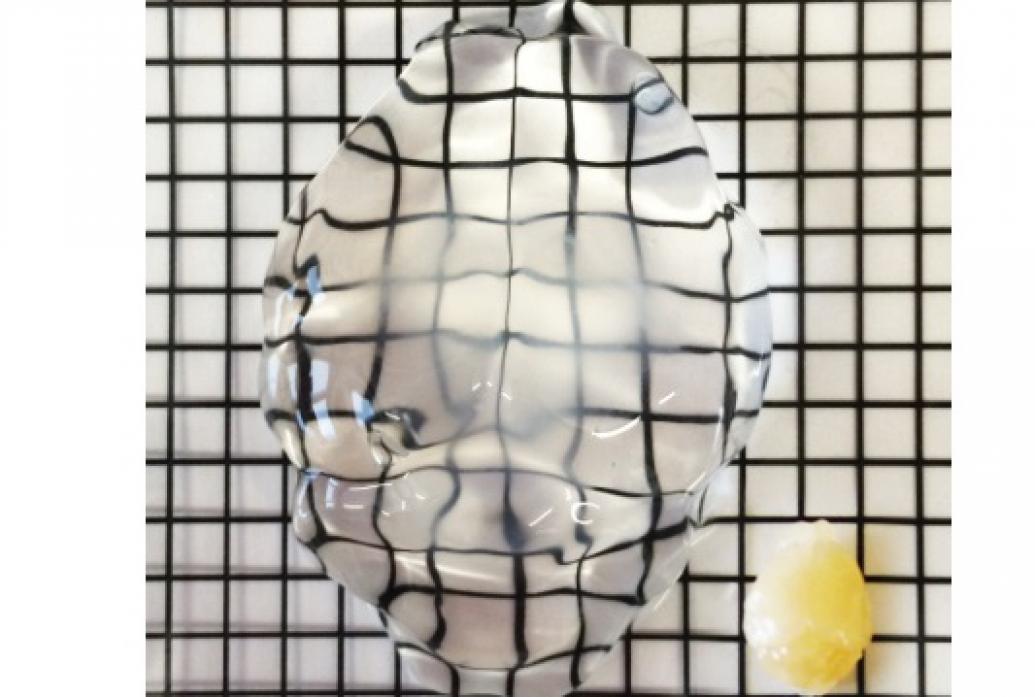

In 2016 in Nature Biotechnology, the lab of Kwanghun Chung published the chemical process for processing the tissue to become “size adjustable” while still preserving all the internal structure and proteins a neuroscientist might want to see at different scales. The process involves soaking the brain (or other organ) in a dense gel of acrylamide polymers. Proteins are denatured and become attached to the gel, which then expands to up to five times the original size.

That makes a sizable difference. Though many microscopes are limited to 250 nanometers of resolution, MAP allows for a those scopes to resolve structures down to an original size of 60 nanometers, because it allows those structures to become physically larger.

In 2021 Chung's lab made a major upgrade to the technology, tweaking the chemistry such that many more proteins could be labeled in tissue than before. That allowed new visualizations of synapses.

Above: A mouse brain treated with MAP is clearer and larger than a mouse brain left unaltered (bottom right).