It’s a conference known to be overwhelming, but for the scores of Picower Institute researchers who trekked west, the meeting provided its annual unique opportunity to learn, network and monitor the state of the field. And for the 50 Picower researchers among them who presented research on topics as varied as autism, anxiety and anesthesia, they each had a moment, large or small, to convene an audience around their work.

Omar Costilla Reyes of Earl Miller’s lab took especially great advantage of that opportunity by co-organizing a “minisymposium” on intersections between neuroscience and artificial intelligence. The morning-long meeting Monday Oct. 21 drew what appeared to be a couple of hundred people. They heard from a series of experts, including Reyes himself, who discussed using machine learning to help analyze the importance of different neural signals recorded in the cortex of experimental animals as they carried out cognitive tasks.

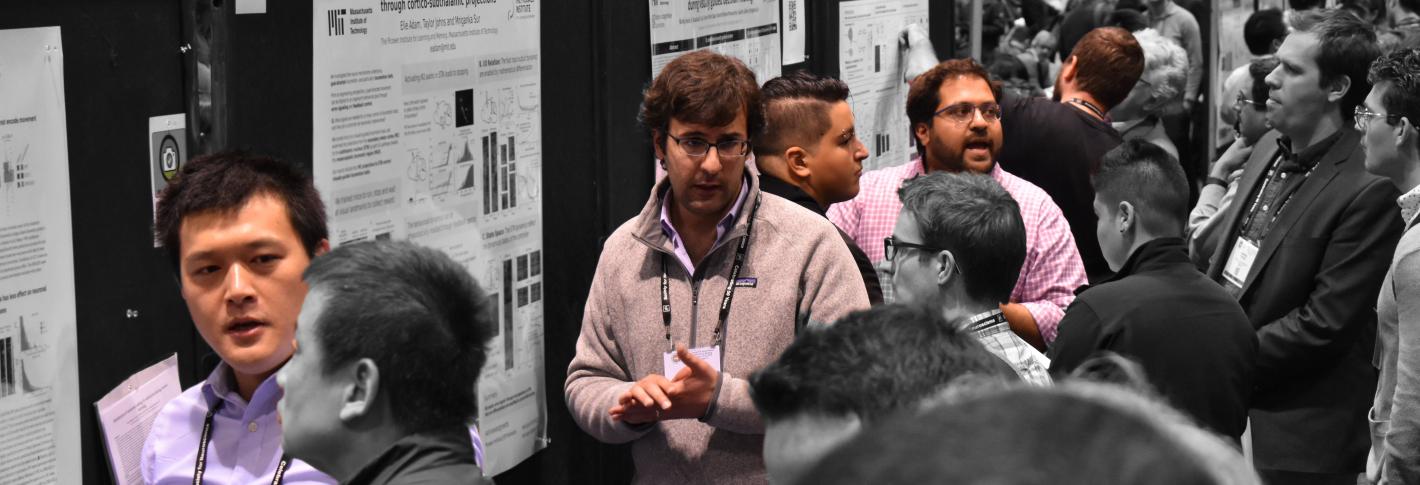

Above: Sur lab members Keji Li, Elie Adam, K. Guadalupe Cruz, Rafiq Huda and Vincent Breton-Provencher present posters all in a row at the Society for Neuroscience Annual Meeting in Chicago Oct. 22.

“I saw the call for mini-symposiums after SfN 2018 and decided to apply with a proposal since I did not see many events at the intersection of AI and Neuroscience last year,” Reyes said. “I was expecting a large group to attend the minisymposium since the intersection of AI and Neuroscience is getting attention from both the computer science community and neuroscience. Also, I thought it was an attractive program since I invited scientists that do not collaborate -- most of them met for the first time at the minisymposium.”

In all, Picower presenters may have reached thousands of colleagues. That number probably became locked in on Tuesday Oct. 22, when Professor Li-Huei Tsai – after an introduction by Professor Emery Brown – took the conference’s main stage for a midday featured lecture on her lab’s research on stimulating the brain’s 40Hz “gamma” rhythms via exposure to light, sound or both to combat Alzheimer’s disease.

BROWSE The Full LIST of Picower presentations and abstracts at SFN19

Tsai lab graduate student Scarlett Barker was among several other Picower researchers who gave talks to sizable audiences. She described her studies of a gene whose enhanced expression amid environmental enrichment may provide a mechanistic explanation for why some people remain resilient to a buildup of Alzheimer’s pathology. Mikael Lundqvist of the Miller lab told his audience that the same specific interplay of neural rhythms the lab has documented in the prefrontal cortex during working memory appears to be a general feature across other cortical areas as well. And Peter Finnie, a Picower Fellow in Mark Bear’s lab, discussed the lab’s work to determine if differences in visual recognition memory – the ability to recognize things as familiar – could prove to be a biomarker for autism spectrum disorders.

Poster outposts

All the conference is a stage, even without a podium. At dozens of posters throughout the five-day conference, Picower Institute researchers held court for hundreds of visitors. Often, they were grouped together forming temporary Midwestern outposts of the Institute.

On Tuesday morning, for instance, Kwanghun Chung’s lab drew a steady crowd of onlookers to a strip of eight posters presenting their latest technology to clarify, enlarge, preserve and label whole brains and tissues to enable unprecedentedly rich imaging and analysis of neurophysiology, development and function. Dae Hee Yun, for example, showed the lab’s rapid whole-brain tissue immunolabeling technology called eFLASH, Katherine Xie presented improvements to the lab’s SHIELD tissue preservation technique and, Yuxuan Tian apprised visitors of a new chemistry innovation to interlock biomolecules to preserve their position in tissues. Many of the lab’s technologies are being integrated, Webster Guan demonstrated, in a pipeline that the lab is using to lead a comprehensive, NIH-funded mapping of the entire human brain.

Several lab members showed how their technologies are applied to a variety of other neuroscience questions, often via collaborations. Chemical engineering graduate student Justin Swaney, for example, detailed the lab’s work to efforts to quantify important differences in the development of cerebral organoid, or “minibrain,” models of diseases such as Rett Syndrome or Zika virus infection. Minyoung E. Kim presented a scalable, end-to-end framework to predict morphological features of microglia and analyze distribution of their subtypes, at whole-brain scale, during development and after Tsai's sensory Alzheimer's treatment. Young-Gyun Park presented a popular poster showing how technologies allowed the Chung and Susumu Tonegawa labs to track down the ensemble of neurons that form a contextual memory, or “engram,” even though it is distributed among many different brain regions.

The Sur lab presented a plethora of posters as well, including five in a row Tuesday afternoon presenting new insights into how cortical circuits and cells represent sensory information and use it to guide movement and behavior. Elie Adam, for example, detailed the multi-regional circuit required for a mouse to halt a sprint as quickly as possible given a visual cue. That’s a behavior familiar to anyone who has watched a baseball player run to a base and stop without going over, or anyone who has poured a drink and stopped before it overflowed.

Similarly lab members K. Guadalupe Cruz and Rafiq Huda teamed up to present a poster showing that the anterior cingulate cortex region of the prefrontal cortex regulates the calculations of another region, the superior colliculus, in visual-stimulus guided decision making and Vincent Breton-Provencher demonstrated how noradrenergic neruons in the locus coeruleus help produce the focus of attention needed to distinguish visual cues amid high uncertainty – much like people must do when driving in bad weather. Ming Hu, meanwhile, presented his work providing a detailed functional mapping of the entire visual cortex and Keji Li presented research by him and Chloe Delepine finding a key role for astrocytes in modulating how neurons encode learning of motor tasks.

The Miller lab, too, occupied a ward of boards on Wednesday morning detailing how neural rhythms reflect and influence cognitive behavior. Lundqvist reprised his talk in poster form. Lab member Roman Loonis demonstrated the neural correlates of keeping an open mind with a poster that tracked how oscillations and neural signals characteristically changed when monkeys tasked with choosing whether one of two images belonged in a category surveyed both options, rather than just one, before making the choice. Scott Brincat, meanwhile, showed how he’s tracked down the means by which the brain’s working memory system rapidly transfers information about a visual stimulus of interest when it moves from the domain of one hemisphere of the cortex to the other.

Two other Miller lab posters, both a collaboration with Brown, combined to present a pair of studies the topic of anesthesia. Jorge Yanar of the Miller lab presented work showing that high-frequency stimulation of the thalamus during some forms of anesthesia can lead to a rapid regaining of consciousness in primates, showing the region’s key role. Andre Bastos described a detailed dissection of how brain wave synchrony changes before and after loss of consciousness, finding how intercortical communication becomes disrupted.

Hot topics

Even when they weren’t grouped into neighborhoods, many other posters showed off the breadth and depth of Picower’s work on a variety of important topics in mental health and fundamental neuroscience.

The poster of Hannah Wirtshafter, formerly of Professor Matt Wilson’s lab, was ordained by the Society for Neuroscience as an official “hot topic.” Her work showed that a region called the lateral septum directly encodes information about the speed and acceleration of an animal as it navigates and learns how to obtain a reward in an environment, making it a hub linking movement and motivation. Wirtshafter and Wilson recently published the study in Current Biology.

The Brown lab had several posters expanding on the topic of anesthesia, including one by Sourish Chakravarty detailing the lab’s efforts to create a closed-loop anesthesia delivery system, based on monitoring brain rhythms, that can help regulate real-time dosing of anesthetic drugs. Pegah Kahali, meanwhile, traced the thalamocortical connectivity patterns that could support the dynamics of coherent alpha rhythms across posterior sensory and frontal cortices as people lose consciousness under propofol anesthesia.

Three posters showed how work in the Tsai lab supported by the new Alana Down Syndrome Center is progressing. Hiruy Meharena discussed how significant physical changes appear to occur within the chromosomes in various brain cell types of people with the syndrome’s three copies of chromosome 21 (trisomy) vs. when they have two copies (disomy). These changes, which appear especially prevalent in neural progenitor cells, occur genomewide and result in substantial differences in gene expression that are associated with brain development. Meanwhile Elana Lockshin focused on differences in glial cells, finding, for instance, that trisomy astrocytes don’t migrate as readily as otherwise similar disomy ones. Consistent with clinical observations and these studies, Yuan-Ta Lin showed how minibrains grown from trisomy stem cells vs. disomy ones have smaller diameters after 30 days of growth and show gene expression differences that may hinder development.

Seven other Tsai lab posters detailed aspects of her Alzheimer’s work, which not only includes studying 40Hz wave stimulation but also how the disease progresses over time and how it is associated with DNA damage. In work to determine the key cell types that allow for visual stimulation of 40Hz rhythms, Chinnakkaruppan Adaikkan presented research indicating that parvalbumin neurons are “indispensable” and somatostatin neurons may play a regulatory role. Brennan Jackson and Noah Milman, members of the team testing 40Hz stimulation with humans, reported early observations from those studies including that the stimulation produces a steady increase in gamma power and functional connectivity in the brains of healthy volunteers and is well tolerated in the trials. Karim Abdelaal, meanwhile presented initial findings in mice that two weeks after stimulation stops, there are still positive effects, including a healthier state of microglia and reduced DNA damage.

Gwyneth Welch and Liwang Liu also presented research on DNA damage in Alzheimer’s in the form of double-stranded breaks (DSBs). Welch’s work has provided new insight into the fate of diseased neurons, including their increased likelihood of an inflammatory response and death in the Ck-P25 mouse model. Liwang Liu, with one of the first posters of the whole exhibition on Saturday, examined an association between DSBs in pyramidal neurons in the hippocampus of Tau P301S mice and hyperexcitability.

Wen-Chin Huang, meanwhile, showed research explaining new findings about the earlier effects of Alzheimer’s. Following up on a recent paper showing that it first emerges in are deep region called the mammillary body, Huang examined specific neuron types there and found that one in particular exhibits hyperactivity in the 5XFAD model of the disease.

Several other posters addressed autism spectrum disorders. Patrick McCamphill of the Bear lab examined whether a promising treatment for Fragile X syndrome may have been hindered by tolerance at the point in the pathway affected by the drug. He described a new intervention that in mouse testing produced benefits without a tolerance effect. Michael Reed in Gloria Choi’s lab described new research that might explain how an immune response to infection sometimes results in a temporary alleviation of symptoms in some individuals with autism. And Vincent Pham of the Sur lab discussed his research on a minibrain model of Rett Syndrome, producing new insights into the molecular pathways underlying the aberrant migration of new neurons.

Two researchers from Professor Susumu Tonegawa’s lab presented studies on fear and anxiety. Andrea Bari described research in mice finding that stimulating neurons in the locus coeruleus could reduce anxiety and help maintain healthier levels of attention when it is impaired by stressful experiences. Xiangyu Zhang, meanwhile showed that fear extinction memories, which override original fear memories, are formed and stored in the basolateral amygdala neurons that are associated with reward.

A rewarding trip

Several researchers reported that the trek to Chicago was worthwhile. Liwang Liu said poster visitors kept him talking non-stop on Saturday for four hours. Throughout the conference, he said, he got good feedback, new ideas and information and even scoped out some new equipment.

His fellow lab member and collaborator Wen-Chin Huang said perhaps 20-30 people visited his Alzheimer’s poster, often asking good questions and providing helpful feedback.

“It is quite an enriching experience,” he said. “I got to know the updated research in the field of memory and Alzheimer’s disease to understand the research directions other scientists are taking to tackle this devastating disease.”

But by Wednesday evening, the massive enterprise of the conference came to an end. The scientists who had flooded in, returned to MIT, newly informed and inspired for the work they’ll perhaps present next year.