The signals that drive many of the brain and body’s most essential functions—consciousness, sleep, breathing, heart rate and motion—course through bundles of “white matter” fibers in the brainstem, but imaging systems so far have been unable to finely resolve these crucial neural cables. That has left researchers and doctors with little capability to assess how they are affected by trauma or neurodegeneration. In a new study, a team of MIT, Harvard, and Massachusetts General Hospital researchers unveil AI-powered software capable of automatically segmenting eight distinct bundles in any diffusion MRI sequence.

In the study in the Proceedings of the National Academy Sciences, the research team led by MIT graduate student Mark Olchanyi reports that their BrainStem Bundle Tool (BSBT), which they’ve made publicly available, revealed distinct patterns of structural changes in patients with Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, and traumatic brain injury and shed light on Alzheimer’s disease as well. Moreover, the study shows, BSBT retrospectively enabled tracking of bundle healing in a coma patient that reflected the patient’s 7-month road to recovery.

“The brainstem is a region of the brain that is essentially not explored because it is tough to image,” said Olchanyi, a doctoral candidate in MIT’s Medical Engineering and Medical Physics Program. “People don't really understand its makeup from an imaging perspective. We need to understand what the organization of the white matter is in humans and how this organization breaks down in certain disorders.”

The gist:

- Nerve bundles in the brainstem are hard to see clearly with brain scans.

- A new AI tool can reliably map eight bundles in the living human brainstem in diffusion MRI scans.

- This technology reveals hidden signs of damage and healing in conditions like Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, multiple sclerosis, traumatic brain injury, and coma.

Added Emery N. Brown, Olchanyi’s thesis supervisor and co-senior author of the study: “The brainstem is one of the body’s most important control centers. Mark’s algorithms are a significant contribution to imaging research and to our ability to understand the regulation of fundamental physiology. By enhancing our capacity to image the brainstem, he offers us new access to vital physiological functions such as control of the respiratory and cardiovascular systems, temperature regulation, how we stay awake during the day and how we sleep at night.”

Brown is the Edward Hood Taplin Professor of Computational Neuroscience and Medical Engineering in The Picower Institute for Learning and Memory, the Institute for Medical Engineering and Science and the Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences at MIT. He is also an anesthesiologist at MGH and a professor at Harvard Medical School.

Building the algorithm

Diffusion MRI helps trace the long branches, or “axons,” that neurons extend to communicate with each other. Axons are typically clad in a sheath of fat called myelin and water diffuses along the axons within the myelin, which is also called the brain’s “white matter.” Diffusion MRI can highlight this very directed displacement of water. But segmenting the distinct bundles of axons in the brainstem has proved challenging because they are small and masked by flows of brain fluids and the motions produced by breathing and heart beats.

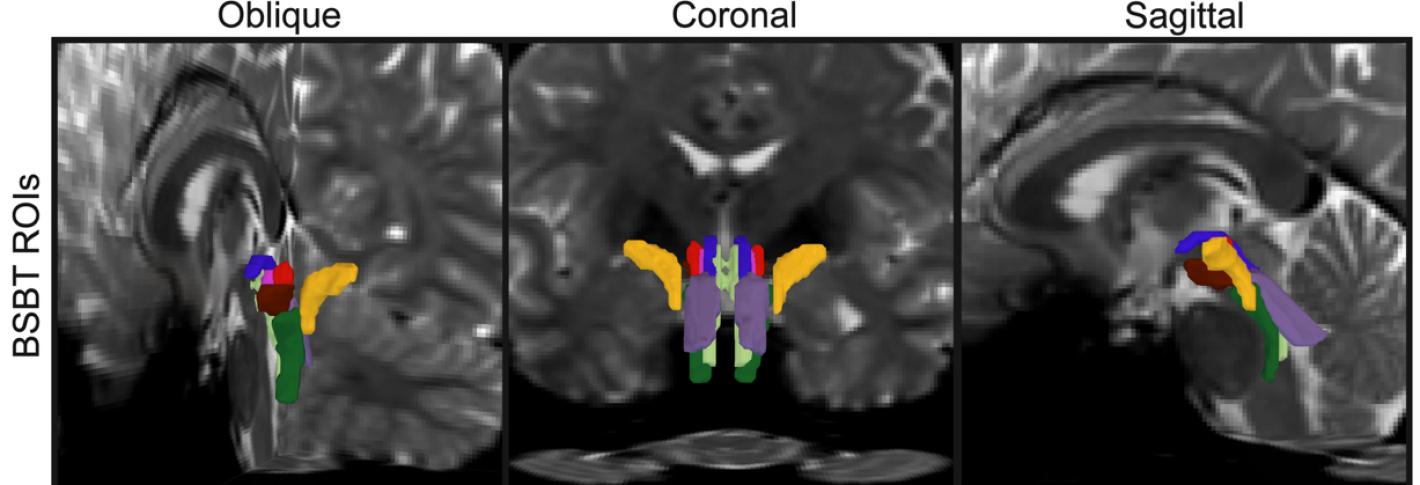

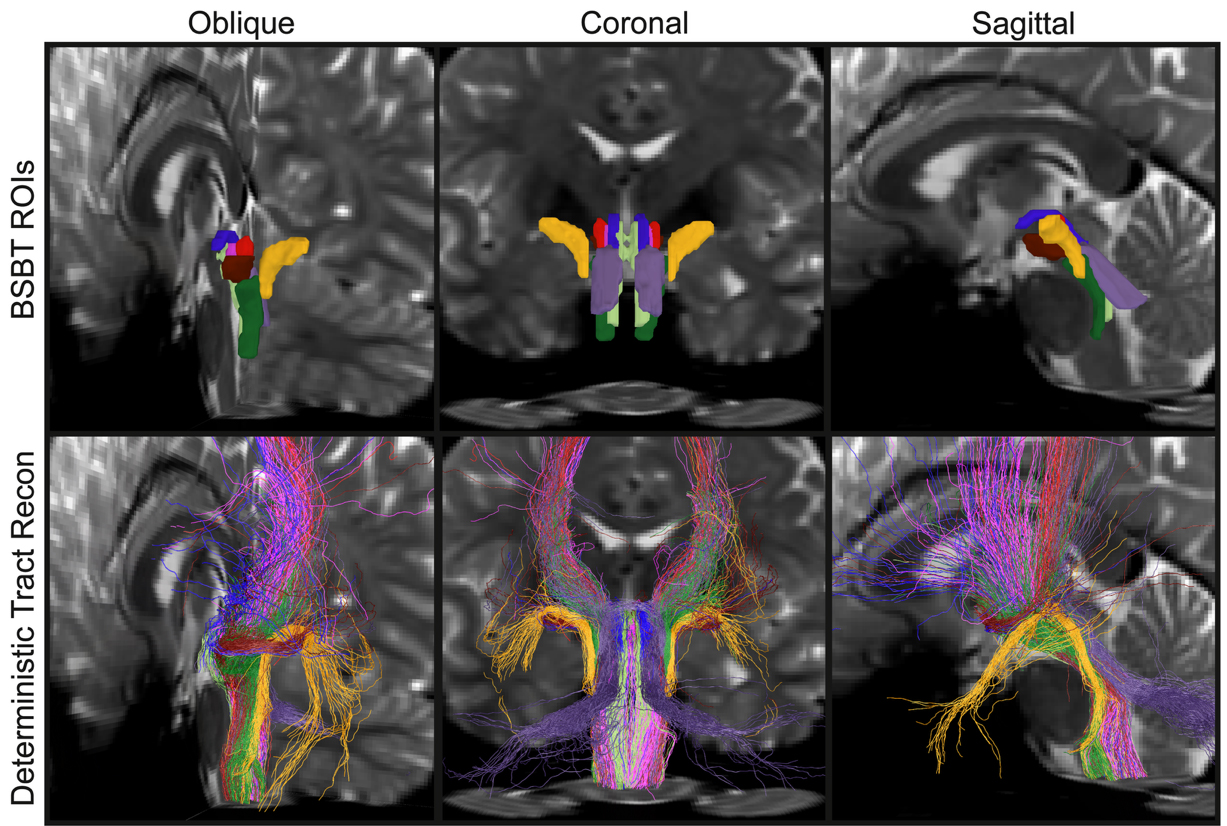

As part of his thesis work to better understand the neural mechanisms that underpin consciousness, Olchanyi wanted to develop an AI algorithm to overcome these obstacles. BSBT works by tracing fiber bundles that plunge into the brainstem from neighboring areas higher in the brain such as the thalamus and the cerebellum to produce a “probabilistic fiber map.” An artificial intelligence module called a “convolutional neural network” then combines the map with several channels of imaging information from within the brainstem to distinguish eight individual bundles.

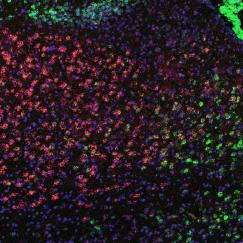

To train the neural network to segment the bundles, Olchanyi “showed” it 30 live diffusion MRI scans from volunteers in the Human Connectome Project (HCP). The scans were manually annotated to teach the neural network how to identify the bundles. Then he validated BSBT by testing its output against “ground truth” dissections of post-mortem human brains where the bundles were well delineated via microscopic inspection or very slow but ultra-high-resolution imaging. After training, BSBT became proficient in automatically identifying the eight distinct fiber bundles in new scans.

In an experiment to test its consistency and reliability, Olchanyi tasked BSBT with finding the bundles in 40 volunteers who underwent separate scans two months apart. In each case, the tool was able to find the same bundles in the same patients in each of their two scans. Olchanyi also tested BSBT with multiple data sets (not just the HCP) and even inspected how each component of the neural network contributed to BSBT’s analysis by hobbling them one by one.

“We put the neural network through the wringer,” Olchanyi said. “We wanted to make sure that it’s actually doing these plausible segmentations and it is leveraging each of its individual components in a way that improves the accuracy.”

Potential novel biomarkers

Once the algorithm was properly trained and validated, the research team moved on to testing whether the ability to segment distinct fiber bundles in diffusion MRI scans could enable tracking of how each bundle’s volume and structure varied with disease or injury, creating a novel kind of biomarker. Though the brainstem has been difficult to examine in detail, many studies show that neurodegenerative diseases affect the brainstem, often early on in their progression.

Olchanyi, Brown and their co-authors applied BSBT to scores of datasets of diffusion MRI scans from patients with Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, MS and traumatic brain injury (TBI). Patients were compared to controls and sometimes to themselves over time. In the scans, the tool measured bundle volume and “fractional anisotropy” (FA), which tracks how much water is flowing along the myelinated axons vs. how much is diffusing in other directions, a proxy for white matter structural integrity.

In each condition, the tool found consistent patterns of changes in the bundles. While only one bundle showed significant decline in Alzheimer’s, in Parkinson’s the tool revealed a reduction in FA in three of the eight bundles. It also revealed volume loss in another bundle in patients between a baseline scan and a two-year follow-up. Patients with MS showed their greatest FA reductions in four bundles and volume loss in three. Meanwhile, TBI patients didn’t show significant volume loss in any bundles, but FA reductions were apparent in the majority of bundles.

Testing in the study showed that BSBT proved more accurate than other classifier methods in discriminating between patients with health conditions vs. controls.

BSBT, therefore, can be “a key adjunct that aids current diagnostic imaging methods by providing a fine-grained assessment of brainstem white matter structure and, in some cases, longitudinal information,” the authors wrote.

Finally, in the case of a 29-year-old man who suffered a severe TBI, Olchanyi applied BSBT to scans taken during the man’s 7-month coma. The tool showed that the man’s brainstem bundles had been displaced but not cut and showed that over his 7-month coma, the lesions on the nerve bundles decreased by a factor of three in volume. As they healed, the bundles moved back into place as well.

The authors wrote that BSBT, “has substantial prognostic potential by identifying preserved brainstem bundles that can facilitate coma recovery.”

The study’s other senior authors are Juan Eugenio Iglesias and Brian Edlow. Other co-authors are David Schreier, Jian Li, Chiara Maffei, Annabel Sorby-Adams, Hannah Kinney, Brian Healy, Holly Freeman, Jared Shless, Christophe Destrieux, and Hendry Tregidgo.

Funding for the study came from the National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Defense, James S. McDonnell Foundation, Rappaport Foundation, American SidS Institute, American Brain Foundation, American Academy of Neurology, Center for Integration of Medicine and Innovative Technology, Blueprint for Neuroscience Research, and Massachusetts Life Sciences Center. Picower Institute Research is supported by The Freedom Together Foundation.