“Working memory is the sketchpad of consciousness, and it is under our control. We choose what to think about,” he says. “You choose when to clear out working memory and choose when to forget about things. You can hold things in mind and wait to make a decision until you have more information.”

To test this hypothesis, the researchers recorded brain activity from the prefrontal cortex, which is the seat of working memory, in animals trained to perform a working memory task. The animals first saw one pair of objects, for example, A followed by B. Then they were shown a different pair and had to determine if it matched the first pair. A followed by B would be a match, but not B followed by A, or A followed by C. After this entire sequence, the animals released a bar if they determined that the two sequences matched.

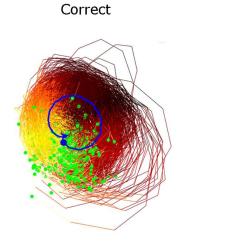

The researchers found that brain activity varied depending on whether the two pairs matched or not. As an animal anticipated the beginning of the second sequence, it held the memory of object A, represented by gamma waves. If the next object seen was indeed A, beta waves then went up, which the researchers believe clears object A from working memory. Gamma waves then went up again, but this time the brain switched to holding information about object B, as this was now the relevant information to determine if the sequence matched.

However, if the first object shown was not a match for A, beta waves went way up, completely clearing out working memory, because the animal already knew that the sequence as a whole could not be a match.

“The interplay between beta and gamma acts exactly as you would expect a volitional control mechanism to act,” Miller says. “Beta is acting like a signal that gates access to working memory. It clears out working memory, and can act as a switch from one thought or item to another.”

A new model

Previous models of working memory proposed that information is held in mind by steady neuronal firing. The new study, in combination with their earlier work, supports the researchers’ new hypothesis that working memory is supported by brief episodes of spiking, which are controlled by beta rhythms. Two other recent papers from Miller’s lab offer additional evidence for beta as a cognitive control mechanism.

In a study that recently appeared in the journal Neuron, they found similar patterns of interaction between beta and gamma rhythms in a different task involving assigning patterns of dots into categories. In cases where two patterns were easy to distinguish, gamma rhythms, carrying visual information, predominated during the identification. If the distinction task was more difficult, beta rhythms, carrying information about past experience with the categories, predominated.

In a recent paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Miller’s lab found that beta waves are produced by deep layers of the prefrontal cortex, and gamma rhythms are produced by superficial layers, which process sensory information. They also found that the beta waves were controlling the interaction of the two types of rhythms.

“When you find that kind of anatomical segregation and it’s in the infrastructure where you expect it to be, that adds a lot of weight to our hypothesis,” Miller says.

The researchers are now studying whether these types of rhythms control other brain functions such as attention. They also hope to study whether the interaction of beta and gamma rhythms explains why it is so difficult to hold more than a few pieces of information in mind at once.

“Eventually we’d like to see how these rhythms explain the limited capacity of working memory, why we can only hold a few thoughts in mind simultaneously, and what happens when you exceed capacity,” Miller says. “You have to have a mechanism that compensates for the fact that you overload your working memory and make decisions on which things are more important than others.”

The research was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health, the Office of Naval Research, and the Picower JFDP Fellowship.

MIT News story