Nervous system functions, from motion to perception to cognition, depend on the active zones of neural circuit connections, or “synapses,” sending out the right amount of their chemical signals at the right times. By tracking how synaptic active zones form and mature in fruit flies, researchers at The Picower Institute for Learning and Memory at MIT have revealed a fundamental model for how neural activity during development builds properly working connections.

Understanding how that happens is important, not only for advancing fundamental knowledge about how nervous systems develop, but also because many disorders such as epilepsy, autism, or intellectual disability can arise from aberrations of synaptic transmission, said senior author Troy Littleton, Menicon Professor in The Picower Institute and MIT’s Department of Biology. The new findings, funded in part by a 2021 grant from the National Institutes of Health, provide insights into how active zones develop the ability to send neurotransmitters across synapses to their circuit targets. It’s not instant or predestined, the study shows. It can take days to fully mature and that is regulated by neural activity.

If scientists can fully understand the process, Littleton said, then they can develop molecular strategies to intervene to tweak synaptic transmission when it’s happening too much or too little in disease.

“We’d like to have the levers to push to make synapses stronger or weaker, that’s for sure,” Littleton said. “And so knowing the full range of levers we can tug on to potentially change output would be exciting.”

Littleton Lab research scientist Yuliya Akbergenova led the study published Oct. 14 in the Journal of Neuroscience.

How newborn synapses grow up

In the study, the researchers examined neurons that send the neurotransmitter glutamate across synapses to control muscles in the fly larvae. To study how the active zones in the animals matured, the scientists needed to keep track of their age. That hasn’t been possible before, but Akbergenova overcame the barrier by cleverly engineering the fluorescent protein mMaple, which changes its glow from green to red when zapped with 15 seconds of ultraviolet light, into a component of the glutamate receptors on the receiving side of the synapse. Then, whenever she wanted, she could shine light and all the synapses already formed before that time would glow red and any new once that formed subsequently would glow green.

With the ability to track each active zone’s birthday, the authors could then document how active zones developed their ability to increase output over the course of days after birth. The researchers actually watched as synapses were built over many hours by tagging each of eight kinds of proteins that make up an active zone. At first, the active zones couldn’t transmit anything. Then, as some essential early proteins accumulated, they could send out glutamate spontaneously, but not if evoked by electrical stimulation of their host neuron (simulating how that neuron might be signaled naturally in a circuit). Only after several more proteins arrived did active zones possess the mature structure for calcium ions to trigger the fusion of glutamate vesicles to the cell membrane for evoked release across the synapse.

Activity matters

Of course, construction does not go on forever. At some point, the fly larva stops building one synapse and then builds new ones further down the line as the neuronal axon expands to keep up with growing muscles. The researchers wondered whether neural activity had a role in driving that process of finishing up one active zone and moving on to build the next.

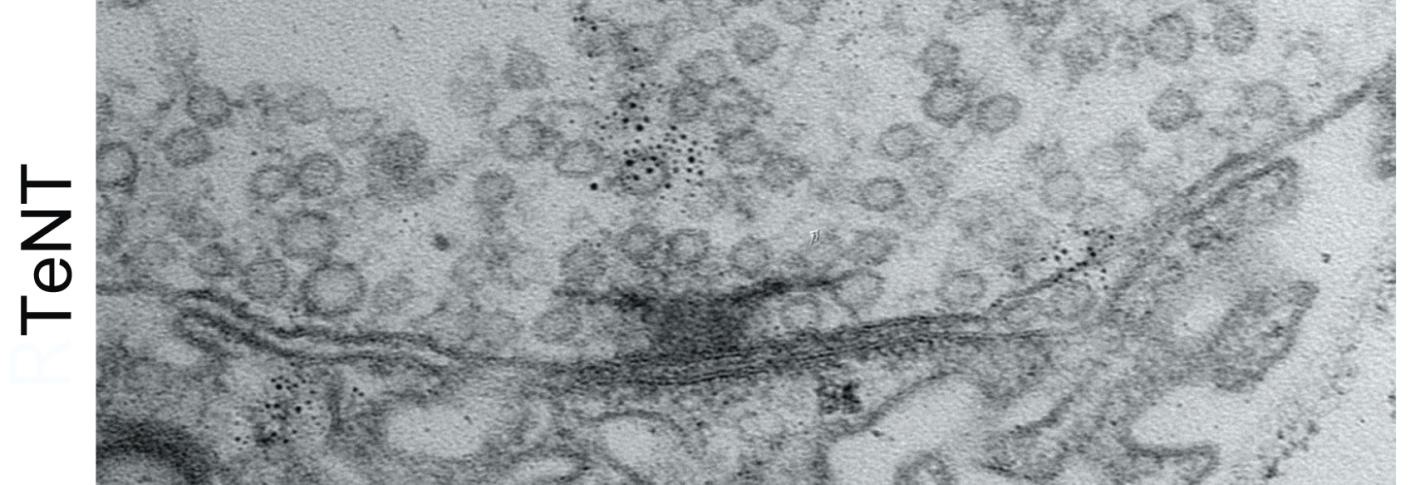

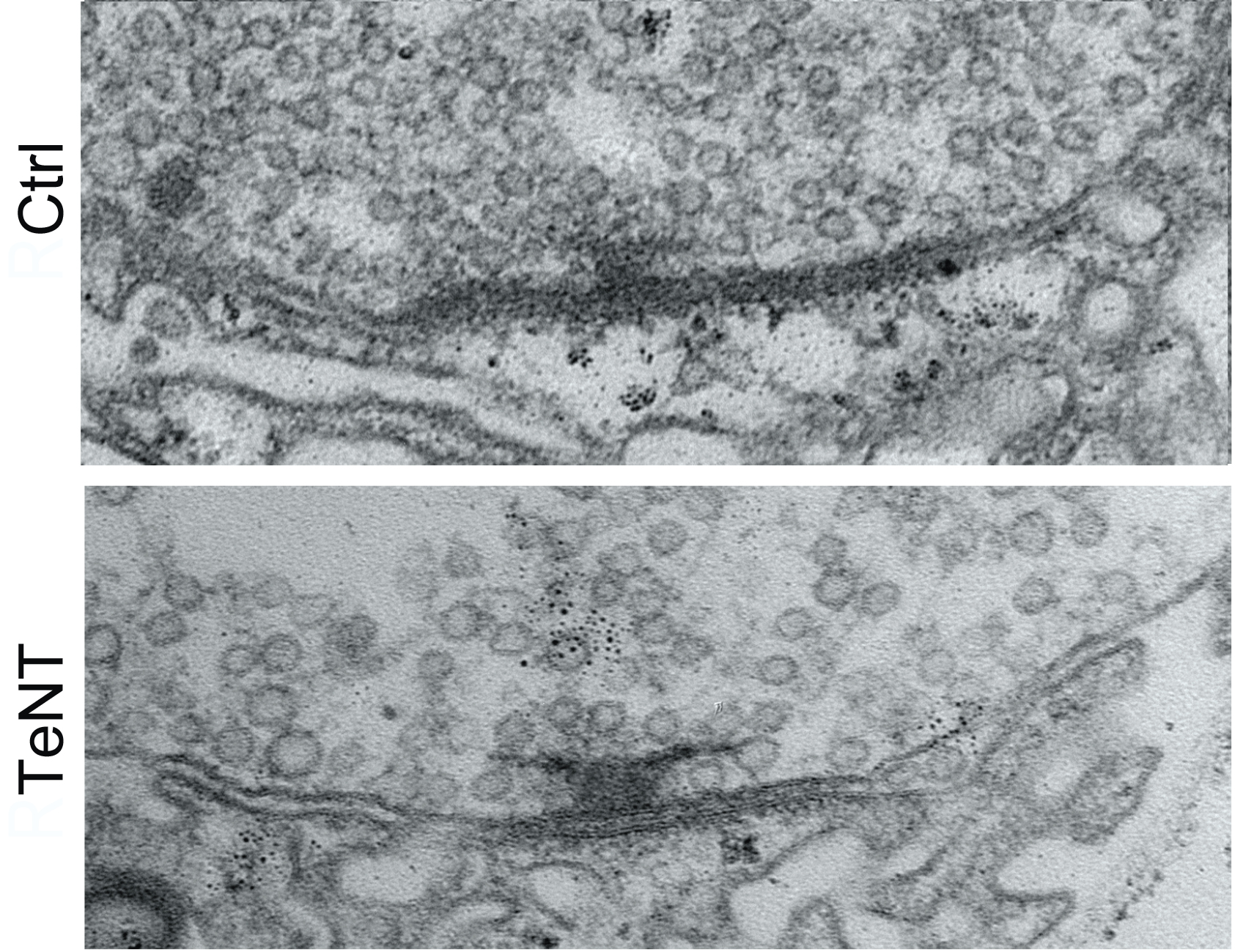

To find out, they employed two different interventions to block active zones from being able to release glutamate, thereby preventing synaptic activity. Notably, one of the methods they chose was blocking the action of a protein called Synaptotagmin 1. That’s important because mutations that disrupt the protein in humans are associated with severe intellectual disability and autism. Moreover, the researchers tailored the activity-blocking interventions to just one neuron in each larva because blocking activity in all their neurons would have proved lethal.

In neurons where the researchers blocked activity, they observed two consequences: the neurons stopped building new active zones and instead kept making existing active zones larger and larger. It was as if the neuron could tell the active zone wasn’t releasing glutamate and tried to make it work by giving it more protein material to work with. That effort came at the expense of starting construction on new active zones.

“I think that what it’s trying to do is compensate for the loss of activity,” Littleton said.

Testing indicated that the enlarged active zones the neurons built in hopes of restarting activity were functional (or would have been if the researchers weren’t artificially blocking them). This suggested that the way the neuron sensed that glutamate wasn’t being released was therefore likely to be a feedback signal from the muscle side of the synapse. To test that, the scientists knocked out a glutamate receptor component in the muscle and when they did, they found that the neurons no longer made their active zones larger.

Littleton said the lab is already looking into the new questions the discoveries raise. In particular, what are the molecular pathways that initiate synapse formation in the first place, and what are the signals that tell an active zone it has finished growing? Finding those answers will bring researchers closer to understanding how to intervene when synaptic active zones aren’t developing properly.

In addition to Littleton and Akbergenova, the paper’s other authors are Jessica Matthias and Sofya Makeyeva.

In addition to the National Institutes of Health, The Freedom Together Foundation provided funding for the study.