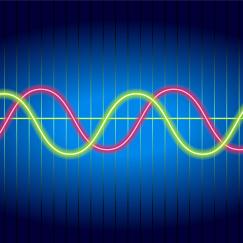

In numerous papers over more than a decade, Brown has helped the field understand how different anesthesia drugs – such as propofol, dexmedetomidine and sevoflurane — interact with various neuronal receptors, affecting circuits in different regions of the brain. Those neurophysiological effects ultimately give rise to a state of unconsciousness – essentially a “reversible coma” – characterized by powerful, low frequency brain waves that essentially overwhelm the normal rhythms that synchronize such brain functions as sensory perception, higher cognition or motor control.

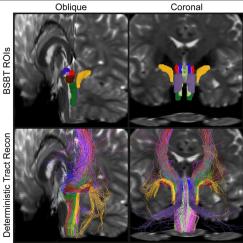

Understanding anesthesia to this degree allows for practical insights. In a study in October 2016 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, for example, Brown and colleague Ken Solt showed how stimulating dopamine-producing neurons in the ventral tegmental area of the brain could wake mice up from general anesthesia. The study suggests a way human patients could be awakened as well, which could lessen side effects, recover normal brain function more rapidly and help patients move more quickly out of the operating room and into recovery.

We should use neuroscience and neuroscience paradigms to try to understand what’s happening in the brain under general anesthesia.

In parallel with illuminating the neuroscience of general anesthesia, Brown has developed statistical methods to finely analyze EEG measurements to the point where anesthesiologists can apply that knowledge to patients. Brown has shown, for instance, that EEG readings of level of unconsciousness vary in characteristic ways based on the drug, its dose, and the patient’s age

“The deciphering of how these drugs are acting in the brain turns out to be an important signal processing question,” Brown said. “The drugs work by producing oscillations, these oscillations are readily visible in the EEG and they change very systematically with drug dose, class and age.”

During the course of every surgery, Brown said, he uses real-time EEG readings to keep a patient adequately dosed without giving too much. In a recent case involving an 81-year-old cancer patient, Brown said he was able to comfortably administer about a third the supposedly needed dose. This can be especially important for older patients.

“We already know you don’t have to give older people as much, but it turns out it can be even less,” said Brown, who is one of the founding investigators of MIT’s Aging Brain Initiative.

Older patients are especially susceptible to problematic side effects when they wake up including delirium or post-operative cognitive dysfunction. Neuroscientifically informed ways to prevent giving too much anesthesia can help prevent such problems, Brown said.

In his latest paper, published last month in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Brown’s group led by postdoctoral fellow Seong-Eun Kim presented a powerful new algorithm for analyzing data sets, like EEGs, where waves vary over time. The SS-MT method produces high-resolution, low-noise spectrograms from such data. In the study, he used SS-MT to discern variations in EEGs with different states of consciousness in patients who had received propofol.

“If we can get clearer, cleaner noise-free measures of the spectrogram then we can infer the states even better,” he said.

Brown said he doesn’t want his methods to stay just with him. To help put the brain at the center of practice, Brown has developed and made freely available training materials at http://www.anesthesiaeeg.com. He is also working to advance these ideas within professional societies.

Ultimately as more anesthesiologists acquire knowledge and EEG equipment, Brown said, and equipment makers produce better displays for their use, the field can move to a model where doctors have a direct view of the patient’s brain when monitoring and maintaining their consciousness during surgery.