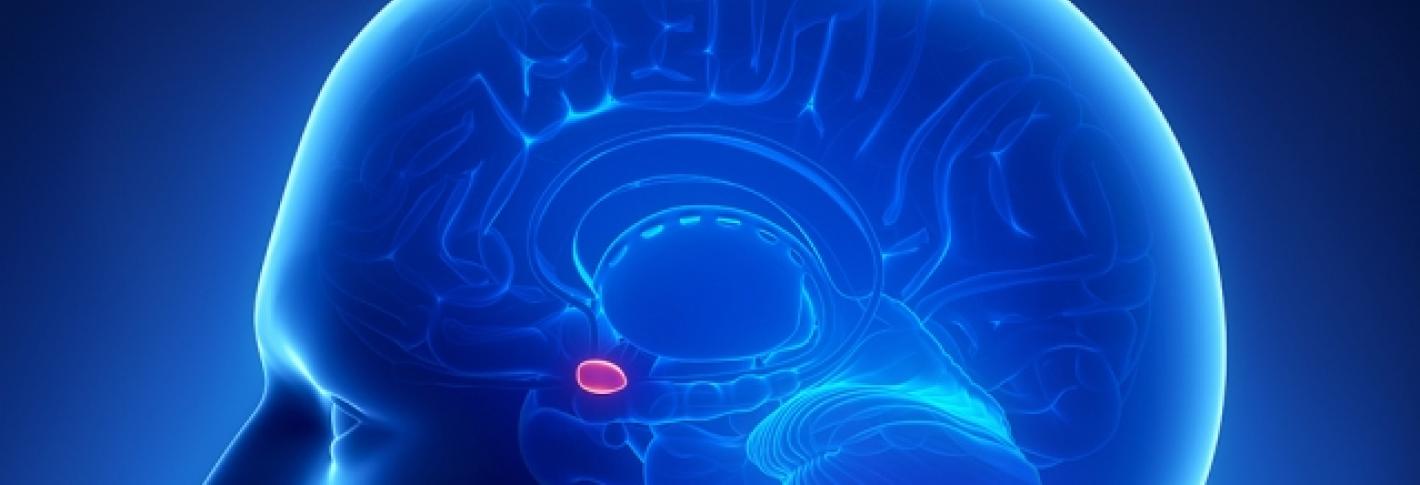

Within a brain region called the amygdala, distinct regions and populations of neurons associate episodic memories with either good (rewarding) or bad (aversive) feelings, or “valence.” The two compete, suppressing each other’s activity. Susumu Tonegawa’s lab hypothesizes that in cases when bad valence neurons gain the upper hand, people can become anxious or depressed.

In several studies between 2014 and 2017 the lab showed that by manipulating these circuits they could change a mouse’s emotional association with specific memories. They have also identified the specific valence neurons within the amygdala, including finding unique markers of genetic expression for each (the genes Ppp1r1b for reward and Rspo2 for aversion). In that line of research, led by former graduate student Joshua Kim, the lab showed that negative memories in mouse models can be prevented by suppressing the activity of the aversive neurons or by boosting the activity of the rewarding neurons.

For these manipulations they have used optogenetics, which adds genes to neurons to allow them to be controlled with flashes of light. These experiments are an innovative proof of concept for a novel therapy for mood disorders. Stimulation could be delivered via technologies that use external electrodes to focus electrical or magnetic fields on relevant sections of the amygdala, or future drugs that can act specifically to suppress Rspo2 or promote Ppp1r1b neurons.

Above: The Amygdala