Neuroscience studies and therapies could each be accelerated if the field had the same kinds of computer simulation tools that benefit computer chip or aerospace designers. Computational models free experimenters from logistical constraints of working with animal models, so they can explore many more hypotheses at the same time.

With those tenets in mind, SUNY Stony Brook Biomedical Engineering Professor Lilianne Mujica-Parodi, who also holds an affiliate appointment in The Picower Institute, conceived of the brain simulation software Neuroblox and assembled a “dream team” of scientists and engineers including MIT neuroscientist and Picower Professor Earl K. Miller, MIT Math Professor Alan Edelman, MIT Research Affiliate Chris Rauckaukas, Stony Brook Associate Professor Helmut Strey, and Dartmouth College Professor Rick Granger. Meanwhile, to launch the effort, she received funding from philanthropists David Baszucki and Jan Ellison Baszucki.

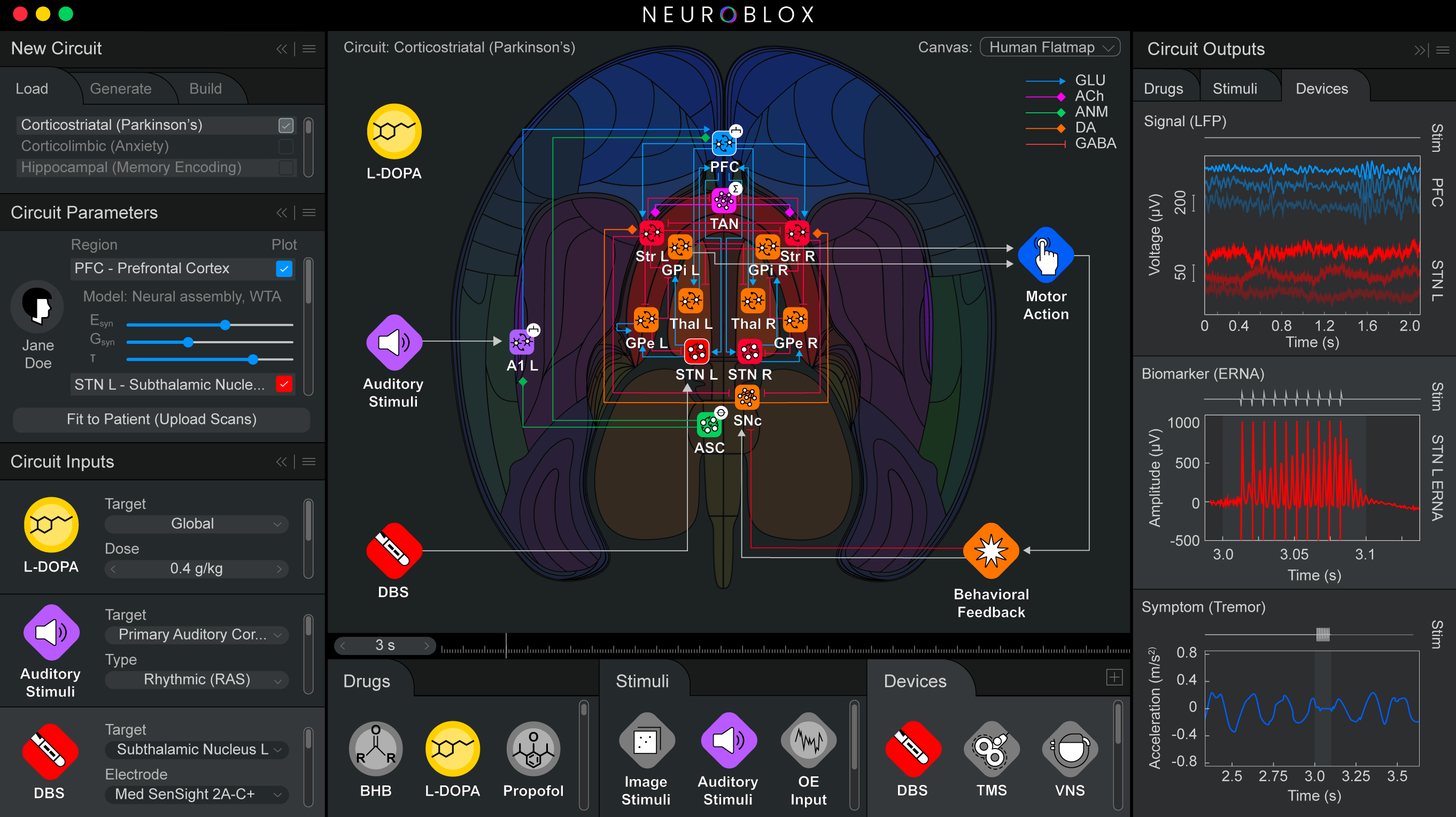

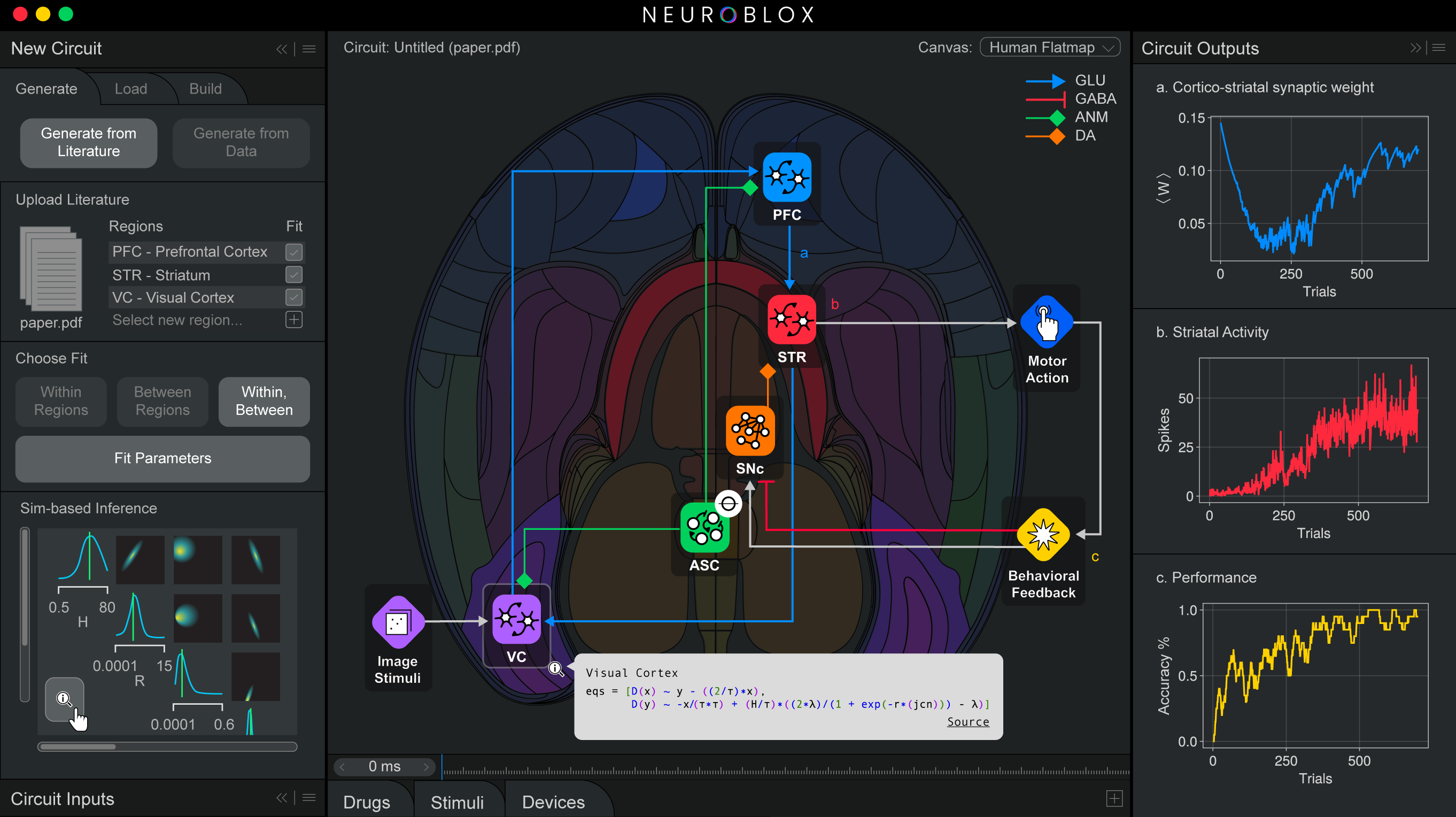

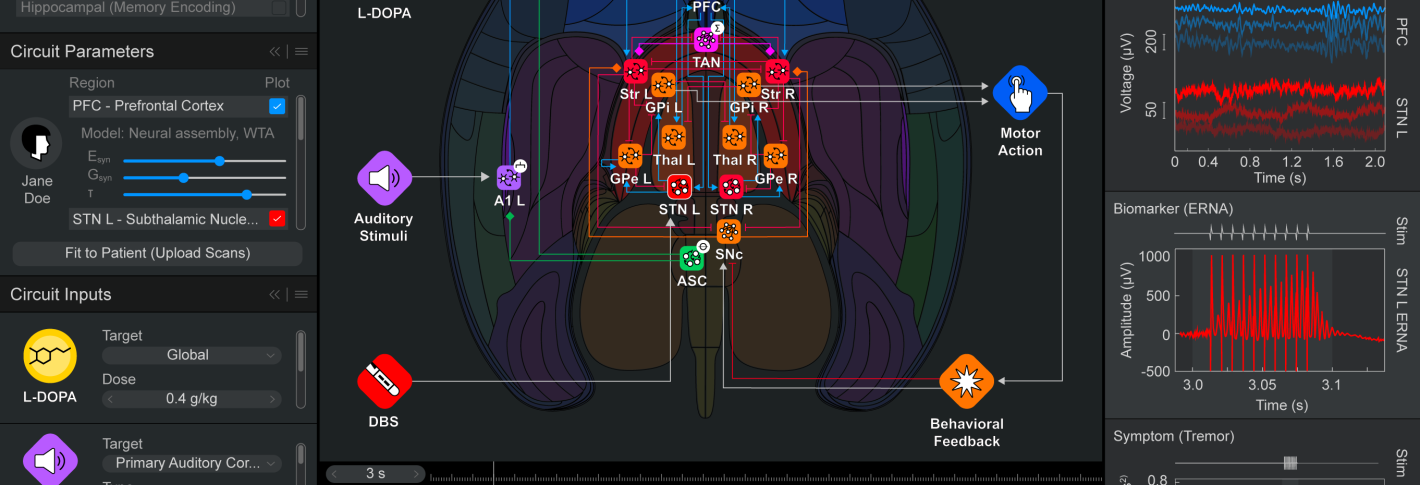

Like an integrated circuit, Neuroblox integrates fundamental computational components, also called “primitives” or “blox.” Unlike a computer chip, Neuroblox is biomimetic, meaning that the blox model fundamental processing units (“primitives”) made up of spiking neurons, experimentally derived from neuroanatomical and neurophysiological data. These primitives are the elements from which larger-scale circuits are composed, which in turn are the elements from which even larger-scale circuits are composed, and so forth. This modular, nested approach—validated against experimental brain data at every scale—extends all the way up to whole-brain computation. Importantly, the virtual neurons in each primitive can respond to electrical or molecular inputs, such as external sensory stimuli, signals from fellow neurons, or neuromodulators such as serotonin, metabolites, or drugs.

The architecture enables the model to connect cellular and molecular activity all the way to cognition and behavior. For instance, in Nature Communications in December 2025, the team published the results of a critical test: They asked Neuroblox to learn a simple visual categorization task that Miller had once asked lab animals to learn. The model did so with almost exactly the same erratic progress that the animals exhibited. Underlying neural activity associated with this learning also closely resembled that of the animals. In fact, the model replicated and therefore revealed something that had remained hidden in the original lab animal data. Some cells, even as learning progresses, continue to inject error. Why? Miller speculates they might give brain the flexibility to discover a new path forward if the rules of the task ever change.

With more recent advances, the company has modeled anesthesia, deep brain stimulation and even questions related to interactions between the central nervous system and other physiological systems, such as how dietary ketosis and diabetic insulin resistance affect the brain.

Below: Example screenshots of the Neuroblox software indicate the program's ease of use and versatility