Neurons communicate electrically, so to understand how they produce such brain functions as memory, neuroscientists must track how their voltage changes — sometimes subtly — on the timescale of milliseconds. In a May 2024 paper in Nature Communications, MIT researchers described a novel image sensor with the capability to substantially increase that ability.

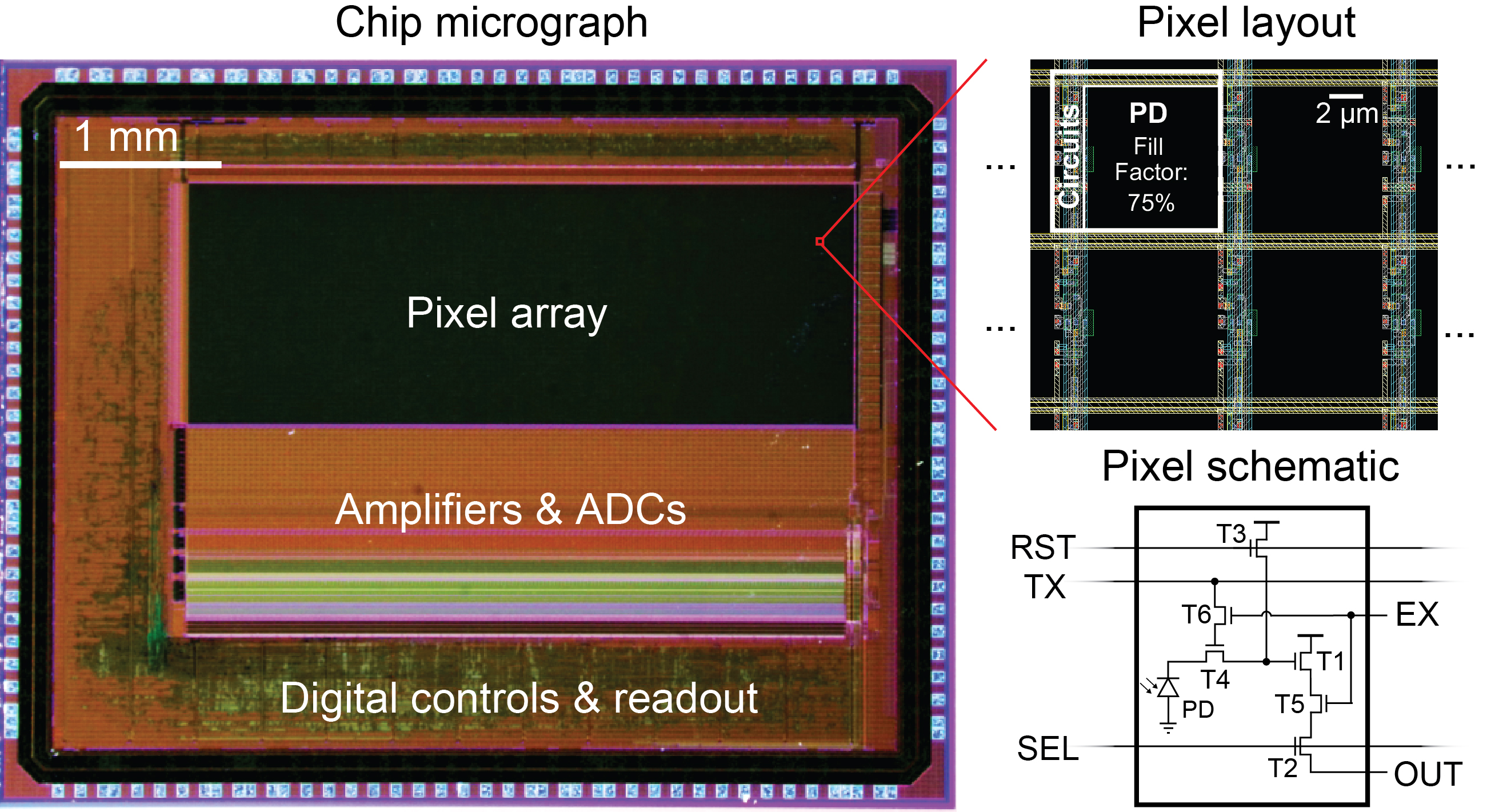

The invention led by Jie Zhang, a former postdoc in The Picower Institute lab of Matt Wilson, is a new take on the standard “CMOS” (complementary metal-oxide semiconductor) technology used in scientific imaging. In that standard approach, all pixels turn on and off at the same time — a configuration with an inherent trade-off in which fast sampling means capturing less light. The new chip enables each pixel’s timing to be controlled individually. That arrangement provides a “best of both worlds” in which neighboring pixels can essentially complement each other to capture all the available light without sacrificing speed. Not only can pixels turn on and off with their own timing, but they can also stay on for varying durations.

In experiments described in the study, Zhang and Wilson’s team demonstrates how “pixelwise” programmability enabled them to improve visualization of neural voltage “spikes,” which are the signals neurons use to communicate with each other, and even the more subtle, momentary fluctuations in their voltage that constantly occur between those spiking events.