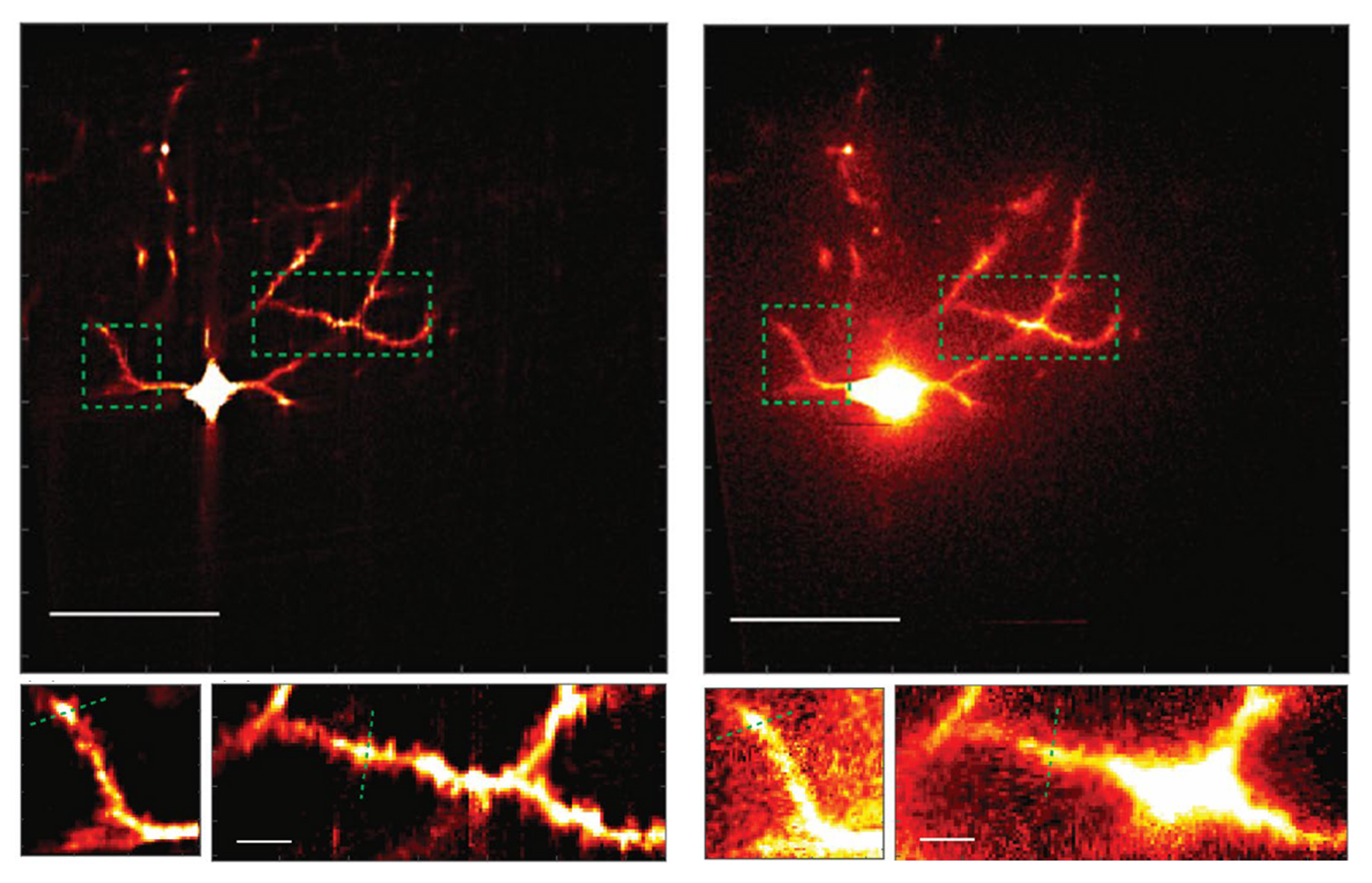

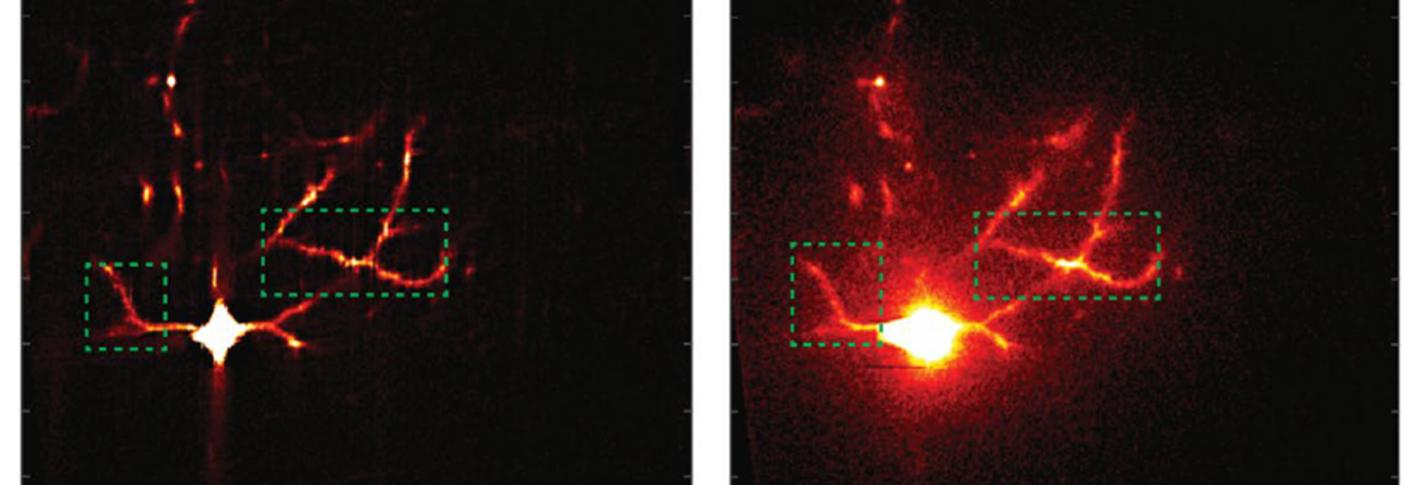

The brain’s ability to learn comes from “plasticity,” in which neurons constantly edit and remodel the tiny connections called synapses that they make with other neurons to form circuits. To study plasticity, neuroscientists seek to track it at high resolution across whole cells, but plasticity doesn’t wait for slow microscopes to keep pace, and brain tissue is notorious for scattering light and making images fuzzy. In 2024 in Scientific Reports, MIT Professors Elly Nedivi and Peter So introduced a new microscopy system designed for fast, clear, and frequent imaging of the living brain.

The system, called “multiline orthogonal scanning temporal focusing” (mosTF), works by scanning brain tissue with lines of light in perpendicular directions. As with other live brain imaging systems that rely on “two-photon microscopy,” this scanning light “excites” photon emission from brain cells that have been engineered to fluoresce when stimulated. The new system proved in the team’s tests to be eight times faster than a two-photon scope that goes point by point, and proved to have a four-fold better signal-to-background ratio (a measure of the resulting image clarity) than a two-photon system that just scans in one direction.

Scanning a whole line of a sample is inherently faster than just scanning one point at a time, but it kicks up a lot of scattering. To manage that scattering, some scope systems just discard scattered photons as noise, but then they are lost, explains lead author Yi Xue, an assistant professor at the University of California at Davis and a former graduate student in So’s lab. Newer single-line and the mosTF systems produce a stronger signal (thereby resolving smaller and fainter features of stimulated neurons) by algorithmically reassigning scattered photons back to their origin. That process is better accomplished by using the information produced by a two-dimensional, perpendicular-direction system such as mosTF, than by a one-dimensional, single-direction system.