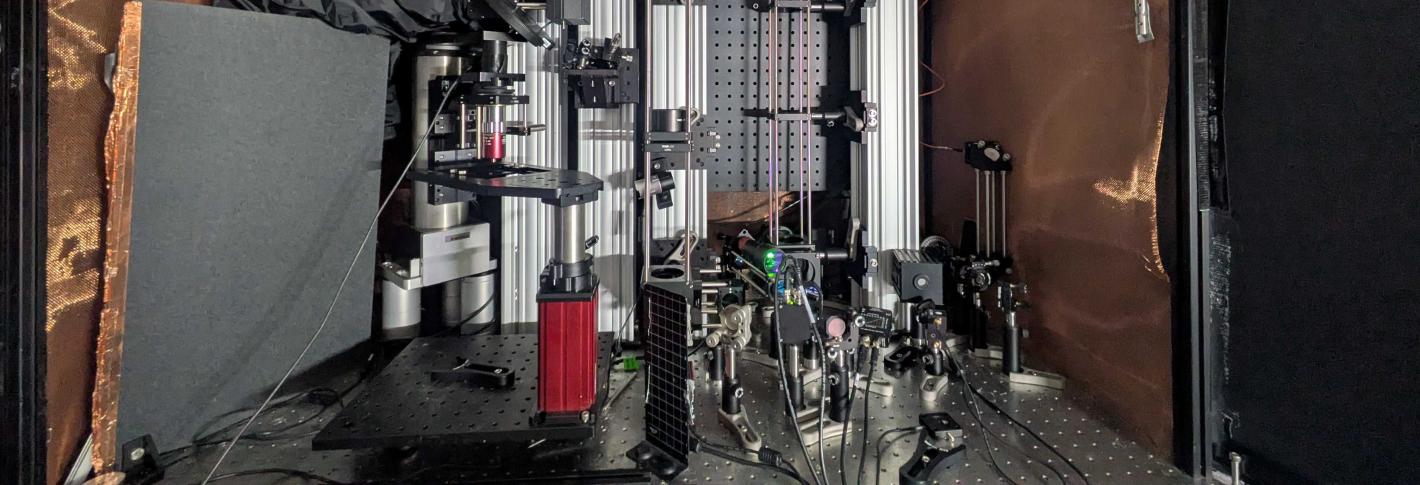

In 2025, a team of MIT scientists and engineers including Professors Mriganka Sur and Peter So along with research scientist Brian Anthony demonstrated a new microscope system capable of peering exceptionally deep into brain tissues to detect the molecular activity of individual cells by using sound.

In the journal Light: Science and Applications, the team led by W. David Lee, Tatsuya Osaki, Xiang Zhang, and Rebecca Zubajlo, demonstrated that they could detect NAD(P)H, a molecule tightly associated with cell metabolism in general and electrical activity in neurons in particular, all the way through samples such as a 1.1-millimeter “cerebral organoid,” a 3D-mini brain-like tissue generated from human stem cells, and a 0.7-milimeter-thick slice of mouse brain tissue.

The new system achieved the depth and sharpness by combining several advanced technologies to precisely and efficiently excite the molecule and then to detect the resulting energy, all without having to add any external labels, either via added chemicals or genetically engineered fluorescence.

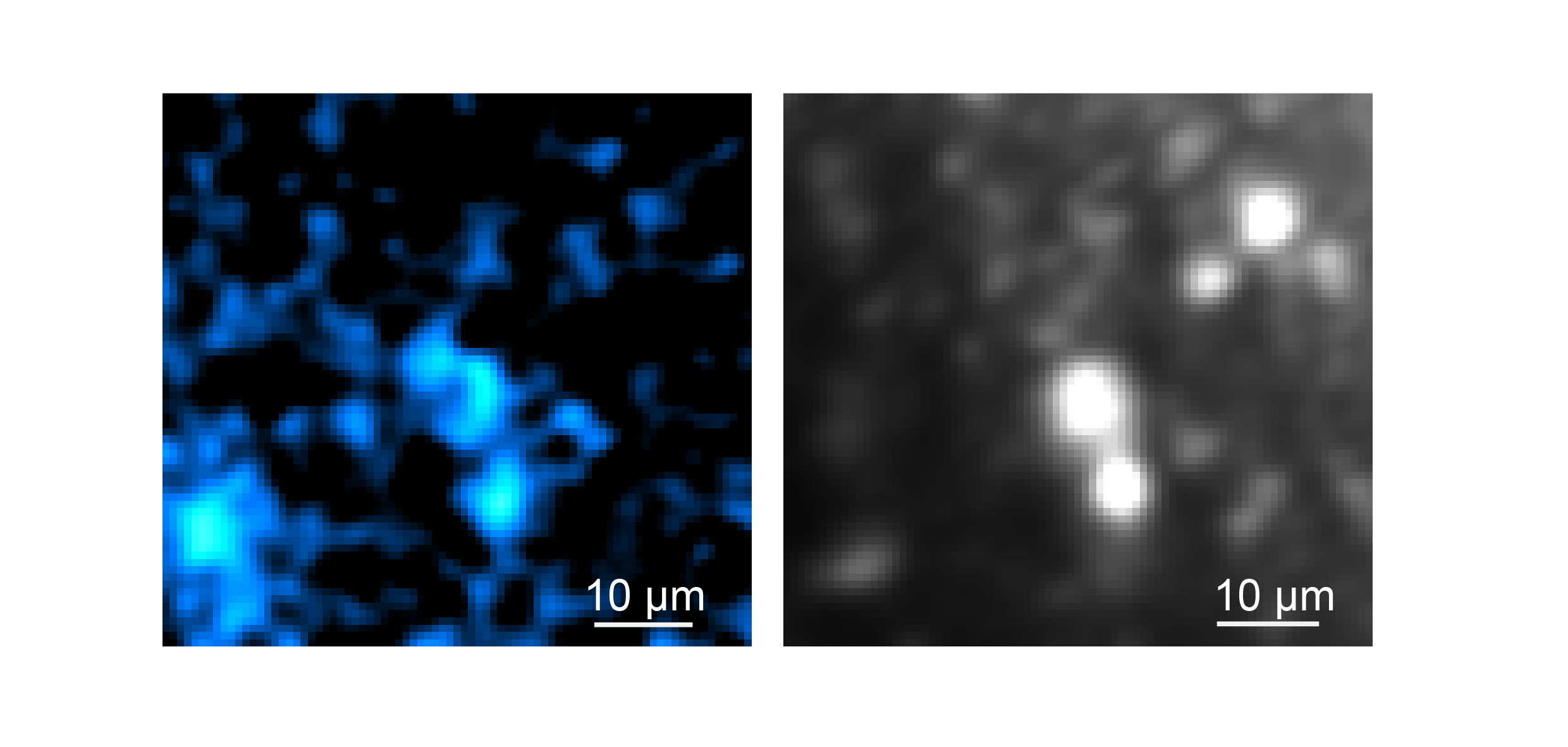

Rather than focusing the required NAD(P)H excitation energy on a neuron with near ultraviolet light at its normal peak absorption, the scope accomplishes the excitation by focusing an intense, extremely short burst of light (a quadrillionth of a second long) at three times the normal absorption wavelength. Such “three-photon” excitation penetrates deep into tissue with less scattering by brain tissue because of the longer wavelength of the light (“like fog lamps,” Sur says). Meanwhile, although the excitation produces a weak fluorescent signal of light from NAD(P)H, most of the absorbed energy produces a localized (about 10 microns) thermal expansion within the cell, which produces sound waves that travel relatively easily through tissue compared to the fluorescence emission. A sensitive ultrasound microphone in the microscope detects those waves and, with enough sound data, software turns them into high-resolution images (much like a sonogram does).