In “monocular deprivation” (MD) experiments, neuroscientists temporarily obscure visual input to one eye of a developing animal, causing a major shift: the deprived eye’s connections to the brain degrade and the undeprived eye takes over. Such experiments starting in the early 1960s produced enormously educational and influential demonstrations of how the brain adapts to experience, a phenomenon called “plasticity.” They also inspired the work of Picower Professor Mark Bear, who has made his own discoveries with direct clinical implications for people who suffer MD naturally in the form of the common vision loss disorder amblyopia.

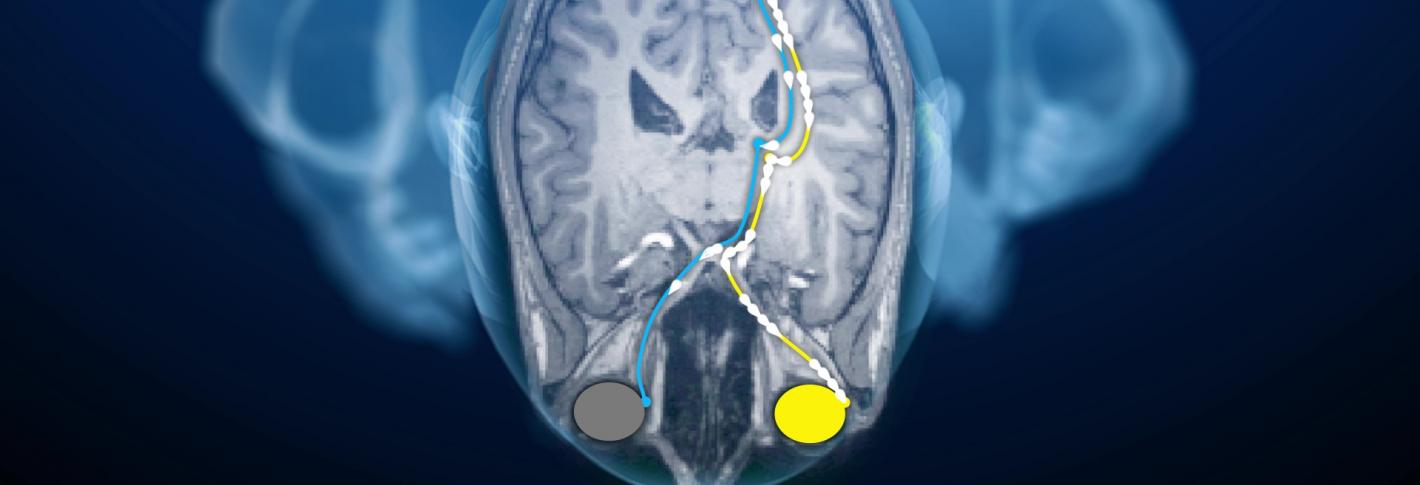

Above: Weak input to the visual cortex from an occluded eye (green) will lead to a shift in neural resources toward input from the unhindered eye (yellow).

Working with theorists at Brown University, Bear had posited and experimentally demonstrated a mechanism by which neural connections would weaken if given weak input, a phenomenon called “long-term depression” or simply LTD. In 2003, a year after he came to MIT, Bear’s lab definitively demonstrated in rats that LTD was the molecular mechanism by which connections supporting a deprived eye lost strength (a result further reinforced in 2009, and subsequently by numerous other labs worldwide).

More than just demonstrating how MD, and therefore amblyopia, alters the circuitry of the visual cortex, Bear’s lab developed a strategy for treating it. Theoretical and experimental work by Bear’s lab helped to reveal that plasticity itself is plastic (a concept called “metaplasticity”). While weak input weakens neural connections via LTD, the complete absence of input appeared to shift the threshold for how much input is instead needed to restrengthen synapses. In 2016 the lab and collaborators put the hypothesis to the test with experiments in which they temporarily anesthetized the retinas of cats and rodents that had been subjected to MD. After the retinas came back online, the vision loss from MD was repaired much better than by traditional patch therapy and at later ages. The team followed up with a study in 2021 showing that only one eye needs to be temporarily anesthetized to achieve this restoration of visual response in the brain.